In the early 1950s there was very little indication of what was in store for the British art world from across the Atlantic. However, LondonersŌĆÖ awareness of developments in recent American painting would soon begin to change. As early as 1953 the Tate Gallery resumed its endeavours to show developments in American art more recent than the work included in the 1946 exhibition American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day. This had showcased the best art from the United States in the previous two centuries and included some modernist artists but not many. This omission was to be remedied a full decade later with Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art.

An avowed Americophile, John Rothenstein, Director of the Tate Gallery, wrote to his counterpart Ren├® dŌĆÖHarnoncourt, Director of New YorkŌĆÖs Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), in October 1953, expressing his belief that an exhibition of twentieth-century American painting in London was long overdue: ŌĆśI expect you are aware it was understood, after the American exhibition which we had here in 1946, that this would be followed by another illustrating more fully than could be done in a comprehensive exhibition, the development of painting in the present century.ŌĆÖ1 Although it is unclear from the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs internal correspondence whether Rothenstein was spurred in any degree by PollockŌĆÖs inclusion in the Institute of Contemporary ArtŌĆÖs Opposing Forces (January to February) and Parallel of Life and Art (September to October) exhibitions held the same year, the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs Director and his colleagues would have been fully conscious of PollockŌĆÖs entry into the British art scene, albeit in a much smaller and less prestigious venue, through these events. Negotiations for a new loan show began in earnest in 1955 and it became evident that a new exhibition that sampled developments in recent modern American art was becoming possible.

In early 1955 MoMA was preparing an exhibition for the Mus├®e dŌĆÖArt Moderne, Paris, which was set to open in April under the title 50 Ans dŌĆÖArt Aux Etats-Unis: Collections du Museum of Modern Art New York.2 Porter McCray, head of MoMAŌĆÖs International Council, and Margaretta Stroup Austin, Information and Cultural Affairs Officer at the United States Information Service (USIS) in the American Embassy in London, worked in conjunction with Rothenstein and Gabriel White of the Arts Council of Great Britain to secure a stop in London for this show after Paris.3 McCray, Rothenstein, White and Philip James, also from the Arts Council, were the central figures who brought the London exhibition to fruition. There was a sense of urgency to offer British viewers a show of this type, as McCray noted in early January 1955: ŌĆśfor some time we have been making the point that London is anxious to see contemporary American work, and it appears that our representations are beginning to bear fruit.ŌĆÖ4

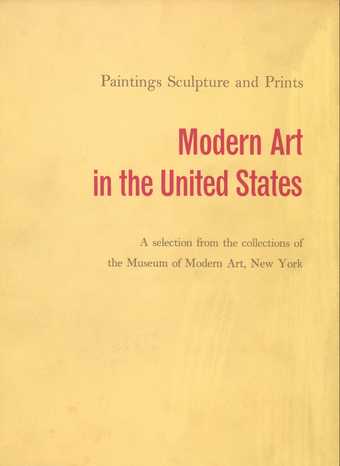

Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art New York opened at the Tate Gallery on 5 January 1956. It was believed that the original French title ŌĆśwas felt to misrepresent the exhibition, inasmuch as some sections were almost exclusively devoted to the post-war periodŌĆÖ, and hence the title for the British showing was changed.5 The long-awaited exhibition was free of admission charge and the Tate Gallery advertised it in daily and weekly papers, including the Times and Observer. Rothenstein stated in a press release, ŌĆśNow that such an opportunity [to show a representative collection of modern American art] has presented itself, the Tate Gallery and the Arts Council are happy to welcome the first big exhibition devoted entirely to painting, sculpture and prints from the United States to come to Great Britain.ŌĆÖ6

Modern Art in the United States featured a large body of work ŌĆō 113 framed paintings, 21 sculptures and over 90 prints ŌĆō and the works, which were displayed in the galleries on white walls, were divided into thematic sections in both the exhibition and the catalogue. According to the catalogue introduction written by dŌĆÖHarnoncourt, the works were chosen ŌĆśto reveal four or five principal directions of American art over a period of approximately forty yearsŌĆÖ.7 He also made a point that later critics and art historians have debated: the exhibition, he stated, reflected the institutional aims of MoMA, particularly of curator Dorothy Miller and director Alfred H. Barr Jr, who selected the works. Reading into dŌĆÖHarnoncourtŌĆÖs words, certain scholars have alleged that New York School art was used, either willingly or covertly, as a weapon of the Cold War.8 Within this perspective, Modern Art in the United States would seem to have inaugurated a scheme by MoMA to use American art, particularly abstract expressionism, as a propagandistic weapon of the Cold War in Europe, acting in concert with the US government.9 Although it can be argued that MoMA sent American painting and sculpture abroad during the 1950s as a symbol of American artistic and political freedom, in both the well-organised sharing of the artworks and what could be seen as the values expressed by the art itself, and thereby as an antidote to communist ideology, this set of motives cannot be said to have precipitated the showing of Modern Art in the United States in London. The Tate Gallery solicited MoMA unsuccessfully in 1946 and then successfully in 1956 for an exhibition of contemporary American art: MoMA did not target the Tate Gallery for propaganda purposes. Furthermore, although the UKŌĆÖs social and economic condition was very fragile immediately following the war, ten years later the country had made a remarkable recovery and was not at risk of a communist coup. MoMA aimed to send to England the best examples of contemporary American art it had, but beyond this it seems unlikely that its intentions were political or propagandistic.

Fig.1

Jackson Pollock

The She-Wolf 1943

Museum of Modern Art, New York

┬® 2019 Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.2

Jackson Pollock

Number 1A, 1948 1948

Museum of Modern Art, New York

┬® 2019 Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

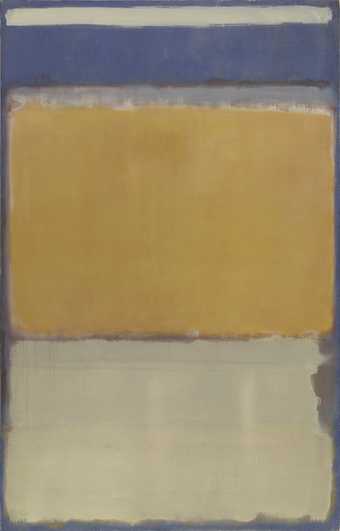

Fig.3

Mark Rothko

Number 10 1950

Museum of Modern Art, New York

┬® 2019 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Paintings and sculpture in Modern Art in the United States were exhibited together, while the printmakers were presented in a separate section. Artists were divided into the following categories: ŌĆśOlder Generation of ModernsŌĆÖ (Charles Demuth, Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, etc.), ŌĆśRealist Tradition: Fact, Satire, SentimentŌĆÖ (Edward Hopper, Charles Sheeler, Andrew Wyeth, etc.), ŌĆśRomantic PaintingŌĆÖ (Hyman Bloom and Morris Graves), ŌĆśModern ŌĆśPrimitivesŌĆÖ (John Kane), ŌĆśSculptureŌĆÖ (Alexander Calder, Ibram Lassaw, Seymour Lipton, Theodore Roszak, etc.) and ŌĆśContemporary Abstract ArtŌĆÖ in the final room of the show. It was in this last group where works by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko were found. Each artist exhibited two paintings ŌĆō PollockŌĆÖs The She-Wolf 1943 (fig.1) and Number 1A, 1948 1948 (fig.2);10 and RothkoŌĆÖs Number 1 1949 (private collection) and Number 10 1950 (fig.3). Over 110 artists in all were selected for the exhibition, and other contemporary American abstract artists included William Baziotes, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still and Mark Tobey.

Fig.4

Catalogue of Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Tate Gallery, London 1956

It is evident from this roster of artists that visitors were afforded a unique opportunity of seeing developments in American art from the early twentieth century to more recent abstract expressionist and social realist works, which were in general less familiar to British and European visitors. There were also a few accompanying public lectures. The leading American art historian and critic Meyer Schapiro spoke on ŌĆśRecent Abstract Painting in AmericaŌĆÖ at the Arts Council on 26 January 1956, as well as presenting a lecture ŌĆśThe Younger American Painters of TodayŌĆÖ for the BBC, while the social realist artist Ben Shahn delivered a talk titled ŌĆśRealism ReconsideredŌĆÖ at the Institute of Contemporary Arts on 2 February 1956.11 In addition, MoMA supplied catalogues to the Arts Council for use in conjunction with the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs exhibition, such as James Thrall SobyŌĆÖs Contemporary Painters (1948), Dorothy MillerŌĆÖs Fourteen Americans (1946) and Alfred BarrŌĆÖs catalogue of MoMAŌĆÖs painting and sculpture collections. The exhibition catalogue itself contained forty-four black and white illustrations and sold over 5,000 copies (fig.4). In it Holger Cahill, former acting director at MoMA, wrote the lead essay, ŌĆśAmerican Painting and Sculpture in the Twentieth CenturyŌĆÖ, which guided readers through a concise art historical survey of the different groupings, phases and types of twentieth-century American art.12

Fig.5

Andrew Wyeth

ChristinaŌĆÖs World 1948

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Press reaction to the exhibition, however, was anything but concise. A striking quantity of articles appeared in a wide range of publications throughout the relatively short duration of the show, which opened on 5 January 1956 and closed on 12 February 1956. The general response to the exhibition was positive. British critics took note of the freshness, strength, variety and provocative nature of the work in the exhibition, although most preferred the older generation of moderns, realists, romantics and primitives over the more recent abstract artists. The realist artists Ben Shahn and Andrew Wyeth were the most favoured, with the latterŌĆÖs ChristinaŌĆÖs World 1948 (fig.5) mentioned and reproduced quite often. Abstract expressionism was the most discussed and controversial part of the show, to the degree that press reviews implied that the work of Pollock, Rothko and their fellow New York School artists comprised most of the exhibition, which was not the case.

Of the approximately twenty-six reviews published in newspapers and journals, most critics at least mentioned the last room of contemporary abstract painting. As PollockŌĆÖs work had been shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1953, many critics were already familiar with it; thus, Pollock was frequently cited as the paradigmatic representative of the new style of painting. The Illustrated London News offered readers a preview of Modern Art in the United States by running a full-page illustrated advertisement highlighting the show, whose significance it claimed was due to the first-time presence in London of current trends in American art.13 Critic Basil Taylor echoed this view, arguing that there had been limited enthusiasm for what was shown in the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs American Painting exhibition in 1946; whereas, now, ten years later, the situation had changed because of the presence of abstract expressionist art. Represented by Pollock, Still, Kline and Rothko, this new style, Taylor claimed, ŌĆśhas gained for the United States an influence upon European art which it has never exerted beforeŌĆÖ, and he believed that what was on view in the last room in the show ŌĆśmay well have important consequencesŌĆÖ.14 Taylor lauded the vigour and energetic rhythm of the abstract canvases.

John Russell offered a completely different assessment in the Sunday Times. RussellŌĆÖs Euro-centric article, ŌĆśYankee DoodlesŌĆÖ, attempted to discredit the New York School by suggesting that the only artists of value in the US were those who were born in or trained in Europe, such as Marsden Hartley or Man Ray. ŌĆśFor the real rude stuff of native American artŌĆÖ, he maintained, ŌĆśwe must look elsewhereŌĆÖ, targeting PollockŌĆÖs painterly techniques with a sarcastic, critical jab. Quoting Cahill, who, in the catalogue essay, noted that ŌĆśPollock affirms the flat space of his canvas by slapping it with his paint-covered handsŌĆÖ, Russell claimed that ŌĆśan interesting work just might be produced by these lowly procedures; but I donŌĆÖt think that, in this case, it was the canvas that deserved the slaps.ŌĆÖ15 The Evening Standard critic sensed a ŌĆśnightmarish elementŌĆÖ in the exhibition, claiming that the organisersŌĆÖ only motive was ŌĆśto prove, apparently, that since 1913 American art has kept in step with European artŌĆÖ.16 The end result of the show, the critic asserted, was a collection of tendencies rather than achievements. The Glasgow Herald presented the work in the show as merely the child of Parisian artistic innovation, an attempt to downplay abstract expressionismŌĆÖs development independent of European art by placing it within a Parisian genealogy. Nevile Wallis of the Observer pointed out that if art can be a signal of a nationŌĆÖs temperament, then prevailing uneasiness was the impression from this exhibition.17 Wallis perceived an air of impermanence in PollockŌĆÖs work, and other critics noticed ŌĆśdisturbingŌĆÖ qualities in the abstract canvases of Pollock and his contemporaries.

Robert Stowe of the Daily Worker, who also favoured the older generation of Americans, alarmingly intoned that ŌĆśthe pointless, slashing violence of these works represents the unconscious suicidal desperation which is one feature of the American sceneŌĆÖ, and he concluded that abstract expressionism was complete nonsense, comparing PollockŌĆÖs abstractions, for instance, to art created by animals.18 StoweŌĆÖs trepidation echoes the Evening StandardŌĆÖs ŌĆśnightmarish elementŌĆÖ comment, and it appears that Stowe and other critics saw an expression of the anxieties of the post-war era within PollockŌĆÖs swirling webs of paint. The Daily Mail confirmed this point, noting that visitors wore unequivocally ŌĆśan expression half of expectation and half of bewildermentŌĆÖ, coupled with a sense of anxiety, though its critic did not identify the source of this anxiety.19

Other writers levelled even more criticism against the exhibition. The ScotsmanŌĆÖs reporter could not understand why works that ŌĆśadd so little to the world art movements should be transported across wide oceans and housed in one of our greatest galleriesŌĆÖ.20 This critic was impressed by the memorable quality of PollockŌĆÖs She-Wolf, but at the same time was perplexed by his skeins of paint in Number 1A, 1948, which, he continued, ŌĆśis like a thousand railway lines, entangled like knitting which has been the plaything of a giant cat. Clapham Junction after a railway accident might have some kinship with a work that is intriguing but puzzling.ŌĆÖ21 Critic T.W. Earp took issue with the catalogueŌĆÖs claim that abstraction released AmericaŌĆÖs true creative forces; on the contrary, he argued, ŌĆśthe forces bombinate in a voidŌĆÖ and ŌĆśnothing is communicated beyond an apparently fortuitous anarchy of pigmentationŌĆÖ in the paintings of Pollock, Still and Motherwell.22 The language of violence, so noticeable in EarpŌĆÖs comments, indicates that this type of reception plausibly stemmed from post-war uneasiness in relation to the threat of nuclear annihilation. Earp apparently viewed PollockŌĆÖs drip canvases as a potentially threatening expression of anarchistic disorder.

Of course, not all the responses were scathing or negative. There was, in fact, a noticeable pattern of dialectical attraction and repulsion in certain reviews, as in the case of the Scotsman article. The ŌĆśshockŌĆÖ of the AmericansŌĆÖ new art should be anything but that, Lawrence Alloway noted in a review that appeared in Art News and Review.23 ŌĆśVisitors to the Tate GalleryŌĆÖ, he argued, ŌĆśwho look at de Kooning, Pollock, Kline, Still and Rothko will be faced by the art of a new aesthetic which, though it is the product of a different culture than ours, is no more alien to us than any other art.ŌĆÖ24 Alloway urged viewers not to see abstract expressionism as foreign, (i.e., American), but suggested rather that they should approach it from a strictly aesthetic vantage point and view it in the context of more familiar British or European abstraction. A steadfast champion of American art, Alloway recognised a general resistance in Britain to painting and sculpture from the US. He made light of a ŌĆścultural tariffŌĆÖ imposed by his fellow critics on American art and then sought to explain clearly to readers the facts, as opposed to what he saw as the myths, about abstract expressionist art.25

In addition to AllowayŌĆÖs defensive observations, there were some other prescient opinions offered by British critics. Anton EhrenzweigŌĆÖs ŌĆśThe Modern Artist and the Creative AccidentŌĆÖ was published in the Listener, a weekly published by the BBC, and broadcast on BBC radioŌĆÖs Third Programme.26 Ehrenzweig defended painters like Pollock from the typical charge of casual doodling by elaborating a conception of the ŌĆścreative accidentŌĆÖ and by invoking Sigmund FreudŌĆÖs notion that most accidents are more purposive than they might appear.27 Denys Sutton also defended Pollock, claiming that ŌĆśthe aim of an artist such as Jackson Pollock, who practises a sort of automatic painting, is to extend the artistŌĆÖs vision; the results may not outweigh the rashness of the means; but the sincerity of the attempt and the gains it may even secure ought not to be despised.ŌĆÖ28 SuttonŌĆÖs approach to Pollock and his contemporaries was reserved and cautious. He believed that time would determine the role America would play in the future art market ŌĆō ŌĆśWhether in the long run America will stand in relation to Europe as Rome did to Greece is, as our American cousins say, the sixty-four thousand dollar question.ŌĆÖ29 However, Sutton was convinced that the Modern Art in the United States exhibition disproved the myth that American modern art lacked exuberance, originality or variety.

Basil TaylorŌĆÖs second article on the exhibition, appearing in the 20 January 1956 issue of the Spectator, echoed his earlier prediction that the abstract canvases in the last room would have lasting consequences. Here he posited a metaphorical link between the new body of painting and the scale and vigour of AmericaŌĆÖs technological enterprise and architectural expansion.30 Furthermore, Pollock, de Kooning, Kline, Rothko and Still, Taylor noted, ŌĆśhave a great technical accomplishment, vitality and considerable formal interestŌĆÖ, and, he warned, ŌĆśthey are not to be written off or treated lightlyŌĆÖ.31 TaylorŌĆÖs double dose of critical acumen stood in stark contrast to the flippant treatment offered by Stowe, Earp or the ScotsmanŌĆÖs unnamed critic. In the 19 January 1956 issue of Country Life, Sutton, like Taylor, followed up his comments cited above with observations on the exhibition in general and the new American painting in particular. The wide variety of styles in the show, he argued, was attributable to the diversity of American culture (i.e., a diversity of people leads to a diversity of styles). Although this point seems rather obvious, Sutton made a more important observation, particularly regarding AmericaŌĆÖs geography and its relationship to the abstract expressionistsŌĆÖ large canvases. He proposed that ŌĆśthe idea of space, in fact, may have ŌĆō as indeed is the case in the United States ŌĆō a wider connotation when the territory is the size of the American land mass.ŌĆÖ32 To American viewers, he continued, it is ŌĆśthe feeling for unlimited space that renders the painting of Rothko or Pollock so intriguing.ŌĆÖ33 Unfortunately, Sutton did not speculate as to what these paintings might mean to British eyes unaccustomed to vast expanses of terrain like that of the American West. The relatively small collection of abstract canvases in Modern Art in the United States certainly made both positive and negative impressions upon British viewers, but SuttonŌĆÖs point was also prescient. Three years later, the Tate Gallery would devote an entire exhibition, instead of a single room, to large abstract expressionist canvases whose size became an important point of discussion among a larger group of critics.

Interestingly, RothkoŌĆÖs work was scarcely mentioned in British newspaper reviews of the exhibition. PollockŌĆÖs name was undoubtedly more familiar than most of the other abstract expressionists in the show. His gestural style had already been discussed in the British press in 1953, whereas RothkoŌĆÖs two canvases in Modern Art in the United States were the first exposure for Londoners to his colour field abstractions. Any substantive critical discussion of RothkoŌĆÖs work before 1956 had taken place in art journals rather than the popular press. His name was known within European critical circles due largely to his participation in the Venice BiennaleŌĆÖs American Pavilion in 1948,34 and within the art press critics such as the artist Patrick Heron were more inclined to address it, unlike other British reviewers who were seeing RothkoŌĆÖs paintings for the first time.

In January 1956 Lawrence Alloway seized another opportunity in the pages of Architectural Design to criticise what he saw as misinformed critics who had failed to interpret the new American art for their public, choosing instead to ŌĆśmuddle and reject itŌĆÖ.35 Alloway identified a fundamental difference between European and American artists, suggesting that ŌĆśthe European tendency is to turn action into connoisseurship, making a fetish of quality which the Americans avoided. There is a world of difference between using materials to record an action and using materials sensuously for the appraisal of well-trained connoisseurs.ŌĆÖ36 He invoked Harold RosenbergŌĆÖs term ŌĆśaction paintingŌĆÖ, coined in his article ŌĆśAmerican Action PaintersŌĆÖ in Art News in December 1952, for this gestural style of painting (in contrast to the colour field work of Rothko and Barnett Newman). He argued that the abstract expressionists in the exhibition were concerned with the events of making a picture, and the personal freedom involved in this process that was dynamic and even anarchistic but without connotations of violence. In this and other articles he published around the time of the exhibition, Alloway stated that he hoped readers would not make the mistake many critics had made in dismissing the new American painting.

By contrast, John Berger, an advocate of social realist art, dismissed unequivocally and vehemently the work of Pollock and his fellow abstract artists in his provocatively titled essay, ŌĆśThe BattleŌĆÖ, published in the New Statesman and Nation.37 Berger claimed (falsely) that in the exhibitionŌĆÖs catalogue and presentation, the abstract expressionists were favoured over the rest of the artists in the show. In reality, ŌĆśContemporary Abstract ArtŌĆÖ was shown in one room and ŌĆśThe Older Generation of ModernsŌĆÖ that Berger favoured were given as much coverage in the catalogue as the more recent artists. More disturbing, however, were BergerŌĆÖs scathing assessments of the abstract expressionists. He asserted that their work had nothing to do with conscious thought or intention and that their paintings were ŌĆśborn only in the violent Act of making marks on the canvasŌĆÖ.38 Furthermore, he stated their canvases ŌĆśare a full expression of the suicidal despair of those who are completely trapped within their own dead subjectivityŌĆÖ.39 Berger could not believe that anyone would take these works seriously, and his language of violence, suicide and despair echoed Robert StoweŌĆÖs comments in the Daily Worker. These socialist-oriented critics seem to have been all too ready to project Cold War anxieties onto American painting, which they believed represented the downfall and degradation of modern society.

One of the most vitriolic reviews of the abstract paintings in the final room of the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs exhibition came from an anonymous critic in the London Times. ŌĆśŌĆ£HeresyŌĆØ of Abstract PaintingŌĆÖ was steeped in a language of negativity ŌĆō ŌĆśbarren confinementŌĆÖ, ŌĆśact of vandalismŌĆÖ, ŌĆśiconoclastŌĆÖ, ŌĆśdecorativeŌĆÖ, ŌĆścripplingŌĆÖ and ŌĆśinsolubly enigmaticŌĆÖ were phrases the author used to describe abstract art.40 The writer, however, offered no concrete examples to support these claims nor was any evidence given as to why abstract art was heretical, apart from his or her individual dislike of it.

More balanced assessments were published in British journals, as well as newspapers, of Modern Art in the United States. After criticising its ŌĆśincoherentŌĆÖ layout in Studio, G.S. Whittet praised Pollock, Rothko, Still and Tobey as ŌĆśbrothers in expression of material qua material ŌĆō large in scale, the impression they give is of paint defining its own design ŌĆō a kind of machina ex machina.ŌĆÖ41 Whittet was impressed by the formal qualities of the work of these artists, as was Robert Melville in Architectural Review. He, too, was appalled by other British criticsŌĆÖ dismissal of ŌĆśthe most mature and civilised paintingŌĆÖ in the Tate Gallery exhibition, and he believed Pollock and company had produced a new kind of painting, not a rehashing of European art.42 Melville also recognised the importance of scale and surface in abstract expressionist works. ŌĆśThese younger menŌĆÖ, he wrote, ŌĆśwork on a larger scale, their paint surface is less dense, more luminous ŌĆ” and in the lyrical art of Pollock, Rothko, Still and Guston it is always a splendid and convulsive mantle.ŌĆÖ43

The most positive assessment of abstract expressionist art in Modern Art in the United States came from the painter and critic Patrick Heron in his Art Digest article, ŌĆśThe Americans at the Tate GalleryŌĆÖ, written for a US audience.44 Heron displayed a critical acumen that was impressive compared to many of his fellow British criticsŌĆÖ dismissive assessments of the AmericansŌĆÖ work. Describing Rothko as ŌĆśthe more important explorer in the groupŌĆÖ and someone who was ŌĆśdiscovering things never before knownŌĆÖ, Heron was the first British critic to write about optical projection and nature metaphors in RothkoŌĆÖs work.45 He observed how, in Number 10 (see fig.3), RothkoŌĆÖs ŌĆśexquisitely powdery horizontal bands of color bulge forward from the canvas into oneŌĆÖs eyes like colored air in strata-form. He evokes the layers of the atmosphere itself.ŌĆÖ46

A comparison of HeronŌĆÖs observations about Rothko to the writings of the ScotsmanŌĆÖs critic about Pollock, where the use of a railway car accident analogy attributed a sense of violence or danger to the latterŌĆÖs work, shows that fundamental differences between these two artists were being discerned in Britain even at this early stage. In fact, Heron criticised PollockŌĆÖs work for the opposite reason he praised RothkoŌĆÖs: he was disturbed by the vortex-like effect of PollockŌĆÖs web of paint skeins: ŌĆśOne never comes up against a resistant planeŌĆÖ, he complained, and added, ŌĆśoneŌĆÖs eye sinks deeper and deeper into the transparency of the mesh.ŌĆÖ47 PollockŌĆÖs treatment of pictorial space bothered HeronŌĆÖs aesthetic sense, leading him to argue that the lack of planes parallel to the canvas itself created a strange denial of spatial experience, whereas RothkoŌĆÖs rectangular planes projected outward in a way that was visually and aesthetically appealing.

Before stating his overall impressions of the abstract expressionists as a group, Heron attempted to counter myths perpetuated in the British press. He asserted with authority that the abstract expressionists constituted a movement that was specifically American and free from European influence. He singled out Pollock as being ŌĆśsuch a seductive artist, as anyone acquainted with the youngest non-figurative painters of Europe or America can testify.ŌĆÖ48 Heron recognised the significance of this group of American painters that many critics had dismissed defiantly. Size, energy, originality, economy, inventive daring, spatial shallowness and direct execution of ideas were qualities in the works that impressed Heron, and he pointed out that the timing of abstract expressionismŌĆÖs arrival in England was important: the exhibition came at ŌĆśthe [right] psychological moment ŌĆō the moment when curiosity was keenest.ŌĆÖ49

Given the amount of attention (both positive and negative) the press devoted to such a small amount of work in the show (twenty-eight abstract canvases out of 127 paintings and sculptures), HeronŌĆÖs conclusion was certainly credible. However, the attention Modern Art in the United States garnered in 1956 would pale in comparison to the amount of press devoted to the Tate GalleryŌĆÖs next major exhibition of American art held three years later, The New American Painting as Shown in Eight European Countries, 1958ŌĆō1959.50 The mid-decade exhibition offered merely a glimpse of what had been developing in the New York art milieu before, during and after the Second World War. In 1959 Londoners would be given the opportunity to assess more comprehensively than ever before the developments in mid-twentieth-century American abstract painting.