Witness Photoworks installation Tate Liverpool 1995

Although the national collection of photographs is held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tate has for many years been acquiring the work of artists who use the camera. In the 1970s, photographic works entering the Collection were often associated with conceptual art, and tended to be records of process or performance. More recently, with the fading of craft-based categories for the visual arts, Tate has responded to a wider range of photographicaly generated art, and the work in Witness stands as evidence of this.

In 1989 Tate Liverpool showed Towards a Bigger Picture, an exhibition of photographs from the V&A which presented the medium in all its diversity. This present display of works from the Tate's own collection focuses on the relationship which photoworks mayor may not have with visual truth: does the artist necessarily witness the image they make? Is the viewer asked to reconstruct a real scene or rather construct a fictive one?

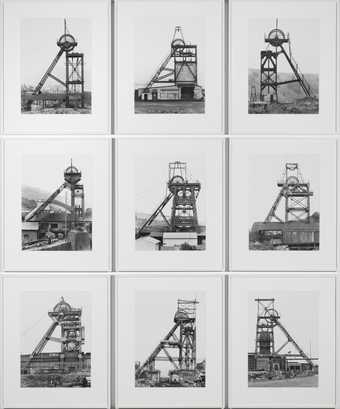

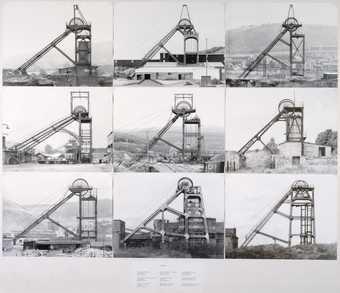

Bernd and Hilla Becher have been enormously influential in the contemporary presentation of photoworks as independent art objects. Their series of photographs began as information for Bernd's paintings but has grown into a widely exhibited collection, a photographic inventory of industrial architecture. Their work literally bears witness to the anonymous sculpture of a rapidly disappearing age: sometimes they photograph a structure moments before its demolition. Historically, photography has often been used to classify, and the Bechers' group their images into various categories and sub-categories: pitheads with one leg, pitheads with two legs, pitheads with one wheel, pitheads with two wheels, and so on. The seeming simplicity of the classifications allows for a presentation of the objects that is as neutral as possible. The Bechers seek to present their photographs impartially: 'We are interested in how people see, we do not want them to look with our eyes but for themselves'.

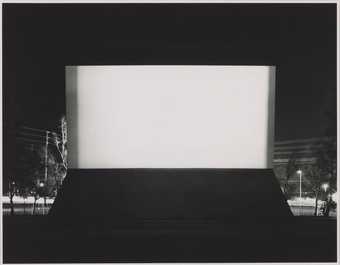

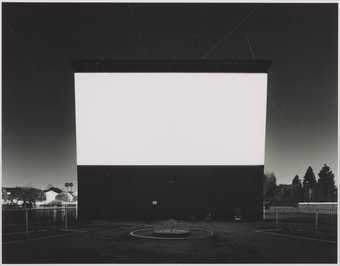

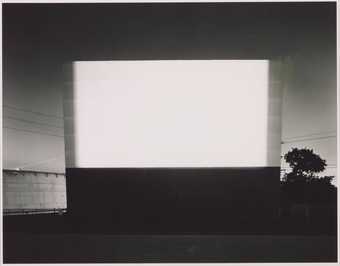

The camera is often seen as an objective means of making of art. However, the eye of the artist inevitably conditions the appearance, as well as the choice of a photowork's subject. Hiroshi Sugimoto also works in series, but his approach is more dramatic than that of the Bechers. He combines a nostalgia for a disappearing, often exotic age with a formal meditation on the passing of time. His works, moments of time fished out of a flow, exploit the fact that the photographic exposure actually contains time within its making. His images of drive-in movie theatres are taken during the projection of a film so that the screen becomes a source of brilliant light, framed by the black of the night sky against which can be seen the trajectories of passing aircraft.

He opens up the gap between the artist and the scene - a gap which exists in all the work in this exhibition, however 'neutral' some of them may seem. The moment in which the scene is photographed is a moment which has passed: each image evokes loss, and is therefore the record of an absence as well as a presence. It is in this paradox that the complexity of the act witnessing is finally contained. The artist witnesses, and it is up to the viewer how to interpret their testimony.