This is the largest and most representative exhibition of Jugoslav art ever held in Western Europe.

To most people in Britain Jugoslav art begins and ends with Ivan Meštrović whose exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1915 at once aroused the liveliest interest. In 1918 his work was again shown at the Grafton Gallery, together with that of another Dalmatian sculptor, Toma Rosandić and the Croatian painter Frano Rački. Jugoslav sculpture and painting is the first collective exhibition of Jugoslav art to be held in this country.

Even before the coming of the Serbs and Croats, the Greeks and Romans had left many artistic traces in the Balkan Peninsula: to quote but a single notable instance, the Palace of Diocletian at Split (Spalato) has created a special tradition of its own.The Jugoslavs, who settled in their present home in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, were from the first under the twin but rival influences of Byzantium and Rome. Under the Nemanja dynasty (thirteenth and fourteenth centuries) architecture and fresco painting flourished exceedingly in Serbia (witness the wonderful churches of Dečani, Gračanica, etc.), until it was harshly arrested by the Turkish conquest in 1459.

Meanwhile Italian, Byzantine and native Slav influences were blended in the ecclesiastical and domestic architecture of the Dalmatian and lstrian towns, and this lasted on into the Renaissance along the whole eastern Adriatic coast. Further north, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries came other influences, at first from Venice, but in later times from Vienna, Graz and Pest also. This was the period of baroque, rococo and Bidermeier which left its traces in the Voivodina (South Hungary), Croatia and Slovenia, no less in church decoration than in the life of the local aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Thus there remain two great traditions, the Eastern, deriving from Byzantine and Syrian ecclesiastical art, among the Serbs and Bulgars, the Western, passing from Romanesque through the Renaissance to baroque and later movements, among the Croats and Slovenes, and the Serbs of Hungary.

Thus at this stage in the evolution of Jugoslav Art there could be neither homogenity nor discipline: and indeed this was rendered all the more difficult by the differences of mentality due to the various political systems under which the nation still lived, and the ferment and confusion resulting from this fact. The applied arts were still in their infancy.

Thus at the turn of the ninenteenth century the Jugoslavs as yet lacked continuity of artistic tradition: they possessed no native school of art or society, or indeed any centre which could compete with the great art centres of the west, it was inevitable that art should develop on individualistic lines.

There arose in Zagreb a school of impressionist landscape painters, who in their turn were held in check by such painters as Ljubo BabiÄŤ.

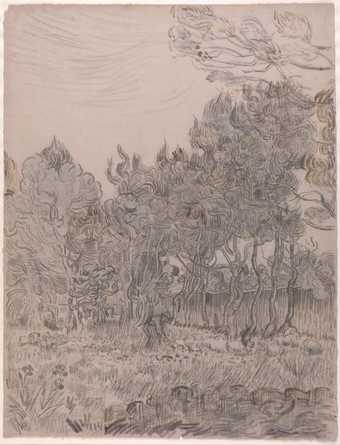

A second group, more colourist in tendency, belongs rather to the school of Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh: its leaders are Branko Popović and Veljko Stanojević.