A distinctive feature of German art is the absence of a consistent tradition. On the one hand this is a disadvantage because the solid persuasive force of French tradition has not been able to prevail; but on the other hand it is an advantage because it has allowed so great a profusion of diverse artistic possibilities to develop. The reason for this is obvious: in Germany there has never been an artistic centre, such as Paris.

There has, indeed, been a local tradition; beginning with °°ùü²µ±ð°ù and Blechen, it was taken up by Menzel arid then handed on to Liebermann and later to Corinth and Beckmann. But at the same time there were other centres in Weimar and Munich, in Dresden and Karlsruhe. In many cases these centres had scarcely any mutual contacts, indeed they regarded each other as adversaries.

The initial situation at the beginning of the great movement of modern art before the First World War was the same. The group of artists in Dresden, Die µþ°ùü³¦°ì±ð (‘The Bridge’), knew nothing of those very similar efforts being made by the Fauves in Paris and made contact with the circle of artists known as Der Blaue Reiter (‘Blue Rider’) in Munich only much later. At the same time Kokoschka was painting his first pictures in Vienna, proceeding from quite different assumptions.

The µþ°ùü³¦°ì±ð group consisted of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1906 they were joined for a time by Nolde and Max Pechstein and in 1911 by Otto Mueller. The group broke up in 1913.

These artists have been called ‘expressionists’, but this name having a certain justification in Nolde’s case, is rather misleading when applied to the others. For it was not so much an intensified expression which they sought as an architectural balance which consisted of simplified forms and violent colours.

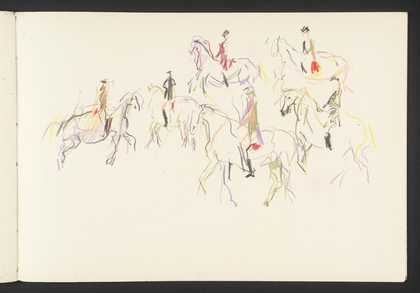

Only a few years later than those belonging to the µþ°ùü³¦°ì±ð group in Dresden, several artists in Munich sought a new approach but with closer contact with general European developments than the former. They soon held their first exhibitions and gave the group the name Der Blaue Reiter. The oldest and, at first, the leading artist of this group was the Russian Wassilij Kandinsky who lived in Munich from 1897 onwards. Other members of this circle were Franz Marc and the Rhinelander August Macke. Paul Klee joined them later.

It was only after 1918 that modern art in general found its way into the museums, but the public at large, which always tends to limp along 50 years behind the times, continued to reject it and was, under Hitler, able to enforce its complete suppression after 1933. It was only after the end of the war that the barriers were removed. The hardships experienced by these artists who either emigrated or continued to work in Germany in order to serve their art, is difficult indeed to estimate.

Alfred Hentzen