Previously on display as part of The Tanks

Many artists challenge traditional ideas around the permanence of art by making works that exist for a limited time

Museums preserve their collections so the artworks can be presented to the public far into the future. But what happens when artists make objects that are meant to change over time or even disappear?

Some artworks rely on the actions of the artist or of other performers to be brought to life. Others include a range of short-lived or temporary materials. For example, Kishio Suga originally made the sculpture Ren-Shiki-Tai in 1973 for an exhibition. He put it together on site in a way that was intentionally fragile and unstable. It was destroyed at the end of the show, and then remade by Suga for an exhibition in 1987. Museum workers reassemble the work every time it is displayed, following the artist’s instructions.

All artworks, even the most robust sculptures, are made of material that changes over the years. Art conservators work to slow down these processes, but sometimes artists actively embrace them. Miroslaw Bałka often makes sculptures that include visibly worn-out objects, such as the partially-used soap bars in 480 x 10 x 10 2000.

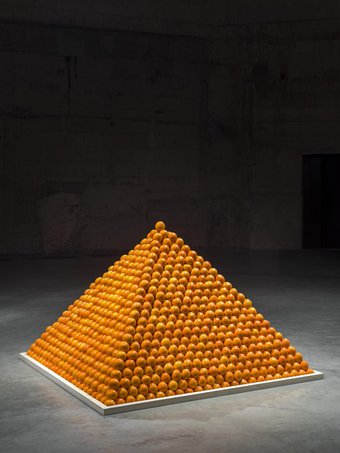

Roelof Louw’s sculpture Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges) 1967 is gradually consumed by the public: each viewer can modify its shape by taking an orange. For the artist, this gesture is both a collaboration and an exchange with the viewers.

Anya Gallaccio works with living materials that decay over just a few weeks. Her installation preserve ‘beauty’ 1991–2003 is made from about 2,000 red gerberas. The cut flowers are pressed against the wall behind four panes of glass. They slowly wilt and fall while they are still on display. Their death is part of the work.

Curated by Valentina Ravaglia

É«¿Ø´«Ã½