Ithell Colquhoun

La Cathédrale Engloutie 1950

Collection RAW (Rediscovering Art by Women). ┬® Spire Healthcare, ┬® Noise Abatement Society, ┬® Samaritans. Photo: Ste╠üphane Pons

Ithell Colquhoun made a significant contribution to British surrealism during the 1930s and 1940s, before forging her own path with her artistic investigations into occultism. In 2019, an important body of her archives and artworks was transferred from the National Trust to Tate. Running to approximately 5,000 items including original sketches and drawings, it is a major addition to Tate ArchiveŌĆÖs existing holdings, which were acquired upon ColquhounŌĆÖs death in 1988 and centre primarily on her esoteric enquiries. Collectively, this extraordinary resource significantly enriches our understanding of ColquhounŌĆÖs motivations for combining her art with magic philosophies and processes. Now, it also forms much of the basis for the exhibition Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds, alongside works from ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs art collection and loans from other public museums and private collections.

The archive contains material relating to ColquhounŌĆÖs developing practice as she engaged with esoteric and surrealist concepts throughout her life. It includes early drawings created while she was studying at the Slade School of Fine Art between 1927 and 1931, and her first forays into magical symbolism and uncanny ŌĆśdouble imageryŌĆÖ. These were created in response to the ideas of Andre╠ü Breton, surrealismŌĆÖs chief theorist spokesperson, and the bizarre dreamscapes of Salvador Dali╠ü that she encountered in Paris during the 1930s. It also includes numerous examples of her extensive experimentation with surrealist automatic methods, in drawings, paintings and poetry executed without conscious control, as well as her visionary representations of the Celtic mythologies of West Cornwall, where she settled permanently in 1959.

Preparations for the exhibition involved detailed analysis of these items alongside the archiveŌĆÖs contextual material, from designs for ceremonies, spells and spiritual workings (such as tesseracts and copies of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram) to letters, literary manuscripts, autobiographical notes and an extensive personal library. In this process, the holdings at Tate Archive have revealed the sheer breadth and depth of ColquhounŌĆÖs groundbreaking career, whereby acts of creation, as much as ceremonial ritual, offered her a legitimate route to personal enlightenment, and even the possibility of wider societal change.

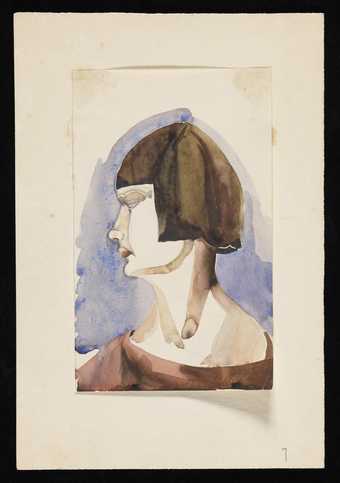

Ithell Colquhoun

Self-Portrait 1929

The Ruth Borchard Collection, courtesy of Piano Nobile, London. ┬® Spire Healthcare, ┬® Noise Abatement Society, ┬® Samaritans

Perhaps most remarkable was that Colquhoun undertook these investigations even when her interest in the occult forced her to break with leading artistic circles. In 1940, having established herself among surrealist factions in Britain and France, Colquhoun was obliged to leave the Surrealist Group in England when its leader, E.L.T. Mesens, specified that members should not belong to any other societies, thus precluding any possibility of joining esoteric orders. ColquhounŌĆÖs departure from a group that included influential figures such as the artist and collector Roland Penrose ultimately resulted in her omission from mainstream histories. Yet the archive confirms that ColquhounŌĆÖs project was much more far-sighted than the concerns of art world factionalism.

While many of those around her sought to limit her creative output to the narrow definitions of British modernism, ColquhounŌĆÖs investigations into the occult demonstrate her unwavering inclination towards universality, and an attempt to uncover more fundamental truths about human existence. Identifying as a surrealist long after her expulsion, she continued to embrace the movementŌĆÖs focus on unconscious dreamworlds, taboo subject matter and psychoanalytic theory to challenge societal conventions. At the same time, she believed in a deeply organised spiritual cosmos and was committed to understanding how she, as an artist and magical seer, could exert influence within it.

The exhibitionŌĆÖs title Between Worlds takes its inspiration from a key tenet in ancient hermetic philosophy that was central to ColquhounŌĆÖs belief system: ŌĆśAs above, so belowŌĆÖ. This doctrine promotes that an essential harmony structures the universe, and that higher spiritual forces are integrally bound up with the material conditions of our earthly realm. If in her professional life Colquhoun was confronting rigid binary oppositions, then the ancient wisdoms she interrogated, including the Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, Egyptian mythology and Hindu Tantra, pointed to the possibility of a single spiritual wisdom and correspondence between all animate and inanimate things.

Ithell Colquhoun

Untitled collage with hands

Tate Archive, TGA 201913. ┬® Tate

By the age of 23, Colquhoun was already positioning herself in relation to this complex theory when she painted a commanding and enigmatic self-portrait situated at the centre of a strange, yet harmonious, natural landscape. Orientating away from the mainstream towards hidden truths and marginal occultist subcultures, Colquhoun seemed entirely comfortable to associate herself with this alternative otherworld, while simultaneously seeking to promote herself within professional circles as a self-confident young painter. Far from seeming contradictory, for her these identities were essential to her persona as a highly individual and visionary artist.

It is important to note that ColquhounŌĆÖs investment in the ŌĆśtheory of correspondencesŌĆÖ had implications beyond her own self-development and spiritual fulfilment. She believed that the universeŌĆÖs mystical forces had a rejuvenating power, and that these energies could be harnessed for the betterment of society more generally. Against the backdrop of 20th-century turmoil caused by imperial domination, sexual prejudice, the rise of fascism and two world wars, Colquhoun saw the potential for magic to bring about a shift in consciousness that would overcome such divisive mindsets. In this project, her art played a fundamental role as a vehicle for promoting her alternative worldview among wider audiences. Alongside her published writings and participation in exhibitions of modern art, Colquhoun sought to nurture greater awareness of esoteric concepts through public-facing projects, an ambition revealed in her designs for occult theatre projects and civic mural schemes, which also feature in the exhibition.

Increasingly, Colquhoun began to recognise the potential synergies between artistic processes and the rituals involved in ceremonial magic and super-natural divination, such as scrying and tarot card reading. A turning point came in 1939, when she became acquainted with a younger group of innovative surrealists, including the British artist Gordon Onslow Ford and Chilean-born Roberto Matta, who were using automatism not only as a way of mining the human psyche, but also to disclose seemingly invisible or ŌĆśhiddenŌĆÖ aspects of the external world. Their approach, captured in MattaŌĆÖs definition of ŌĆśpsychological morphologyŌĆÖ, was central to the evolution of ColquhounŌĆÖs intertwining artistic and occultist practice during the early 1940s.

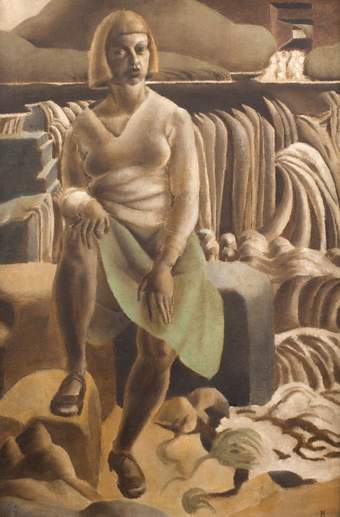

Ithell Colquhoun

Gorgon 1946

Denise and Richard Shillitoe Collection. ┬® Spire Healthcare, ┬® Noise Abatement Society, ┬® Samaritans

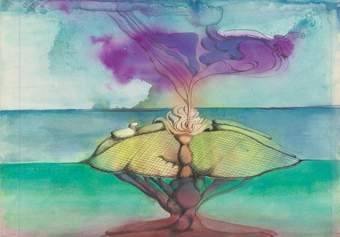

Building upon the idea of automatism as an unconscious mediation of the human mind, she emphasised the importance of what has since been described as ŌĆśtranspersonalŌĆÖ interconnectivity, whereby the individual psyche could connect with other mystic forces existing in different spatial and temporal planes. In this process, which she identified as a mantic form of automatism, that is capable of divination, Colquhoun made conscious adaptations to her spontaneous images, affording agency to the creative mediator who channelled magical power from the spirit world. Writing in her landmark essay ŌĆśChildren of the Mantic StainŌĆÖ, she explained that her own type of interpreted automatism ŌĆśmay proceed along lines of complete abstraction ... Or there may be a hint of natural objects which can be organised and intensified into a designŌĆÖ.

ColquhounŌĆÖs automatic experiments frequently gave rise to vulvic symbolism steeped in the natural landscape that was, to her, communicative of sacred female power. Between Worlds includes intuitive compositions that demonstrate her interest in this ŌĆśdivine femininityŌĆÖ, such as Gorgon 1946, a key example of decalcomania ŌĆō a technique in which paper was pressed onto the canvas while the oil paint was still wet to create a chance mirror image. Gorgon will be shown alongside its related counterpart or ŌĆśpeelŌĆÖ for the first time.

As a practising occultist, Colquhoun embroiled herself in an immersive self-education of multiple theories and curriculums, using drawings and diagrams as a way of working through her responses to the major esoteric teachings of the period, particularly as they were subscribed by the clandestine society, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Adjacent to her experiments in mantic automatism, she was deeply engaged in structured activity that blended contemporary scientific theory with key tenets drawn from ancient wisdoms. She studied the hyperspace philosophies of theorists such as Charles Hinton and P.D. Ouspensky together with different spiritual systems, including the Kabbalistic Tree of Life and the energy points found in Tantric yoga. Her drawings are replete with hermetic symbolism, bodies engaged in sacred sexual union often delineated by flowing energy channels, and pictorial representations of fourth-dimensional space in the form of tesseracts. It seems that Colquhoun was largely creating this work for private contemplation and her own spiritual progression. Nevertheless, it is extraordinarily accomplished in its demonstration of anatomical figuration, solid compositional arrangements and striking colour combinations, which bear the trace of her academic training at the Slade.

Ithell Colquhoun

Surfacing Force 1947

All Tate Archive, TGA 201913. ┬® Tate

ColquhounŌĆÖs discoveries fed back into artworks that she created for public reception, adding new layers of meaning to her work. Several images from her symbolic sex magic sequence Diagrams of Love 1941ŌĆō2 were worked up for inclusion in exhibitions, while the entire series gave rise to poems, one of which was published in the journal The Glass in 1953. During the same moment of intense creativity in the early 1940s, Colquhoun integrated her magical findings into a new group of paintings and drawings that she created in response to CornwallŌĆÖs Druidic mythology and the mystical properties of its ancient stone circles. Beyond Celtic folklore, a diverse set of occultist philosophies stood behind her complex portrayals of Cornish megaliths. In The Sunset Birth c.1942, a womanŌĆÖs body passes through the centre of the tripartite stone configuration M├¬n-an-Tol, her form defined by nothing more than the coloured energy currents of the Tantric chakra system, while in Dance of the Nine Opals 1942, the magically infused standing stones function as extra- dimensional portals to an enlightened spiritual realm.

As these paintings demonstrate, in the ancient, mystic land of West Penwith, Colquhoun was able to embed her magical concepts in a specific place for the first time. Having travelled intermittently between London and Cornwall since the war years, she established a studio in Lamorna Cove in 1949 and relocated permanently to the area a decade later, when she settled in the small village of Paul near Penzance. Though she continued to participate in exhibition forums, notably the group shows of the international occult-surrealist collective Fantasmagie, her attention was primarily directed towards her membership of esoteric orders, many of which placed importance on ceremonial magic.

Ithell Colquhoun

Dance of the Nine Opals 1942

The Sherwin Family Collection permanently housed at The Hepworth Wakefield (Wakefield, UK). ┬® Spire Healthcare, ┬® Noise Abatement Society, ┬® Samaritans

As always, her commitment to the occult filtered back into her art. In 1977 she achieved perhaps the greatest synthesis of these interconnected interests when she created designs for a pack of tarot cards and a related series entitled The Decad of Intelligence. Employing a spontaneous drip technique using vibrant enamel paints, her abstract motifs were intended as direct aids to spiritual transcendence, which conflated the freedom of unconscious automatism with the ordered structure of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram and precise Golden Dawn colour theories.

Soon after its creation, the tarot pack was exhibited at the Newlyn Gallery in Cornwall, demonstrating ColquhounŌĆÖs ambition that her designs should engender a wider engagement with occultism, beyond her own personal enlightenment. Now held by Tate Archive, and on show in Between Worlds for the first time since their display in Newlyn, these visionary works are today being presented for new generations who are finding fresh meanings in ColquhounŌĆÖs multi- layered artistic and magical practice.

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds, Tate St Ives, 1 February ŌĆō 5 May 2025.

In partnership with Lockton. With additional support from the Ithell Colquhoun Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council and Tate Members. Curated by Katy Norris, Curator, Exhibitions and Displays, Tate St Ives with Emma Sharples, Collaborative Doctoral Partnership Researcher, in consultation with Dr Amy Hale, Honorary Research Fellow at Falmouth University, Professor Alyce Mahon, Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Cambridge and Dr Richard Shillitoe, Independent Writer and Researcher.