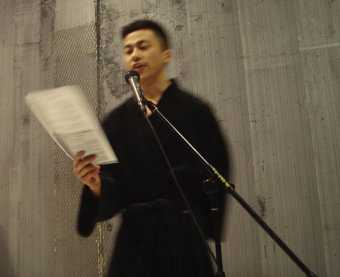

Fig.1

Loo Zihan performing Cane at Defibrillator Performance Space, Chicago, February 2011

In a timely response to the growing interest in ŌĆśnewŌĆÖ art from Southeast Asia, Nora TaylorŌĆÖs paper ŌĆśPerformance as Site of Memory: Performing Art History in Singapore and VietnamŌĆÖ considers the role of artistic practice in the formation of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art history. Weaving connections between site-specific performances, socially engaged exhibitions, artist-led archival projects and participatory installations, Taylor raises important questions around the social agency of performance and performative art in Southeast Asia. Naming these practices ŌĆśsites of memoryŌĆÖ, Taylor explores how performance has surfaced as a means of ŌĆśenacting and enabling public engagement with art-historical knowledgeŌĆÖ.

Commencing with an enquiry into the relationship between performance art and public memory, Taylor presents two iconic works in Vietnamese and Singaporean performance art history: Trß║¦n Anh Qu├ón and Nguyen Van TienŌĆÖs durational performance from 1997 at the Van Mieu complex in Hanoi; and Josef NgŌĆÖs Brother Cane 1993ŌĆō4, performed in the Fifth Passage of Parkway Parade in Singapore. Through a reading that stresses the political implications of both performances respectively ŌĆō Quan and TienŌĆÖs performance as a site-specific inquiry into moral education in Vietnam, and NgŌĆÖs enactment as a protest piece against the mistreatment of homosexuals in Singapore ŌĆō Taylor argues that the aftermath of these events has come to overshadow the performances themselves. In both instances, the performances led to the artistsŌĆÖ arrest for public indecency, enshrining both works in controversy. Public memory of the performances was maintained through a limited selection of photographs ŌĆō notably one capturing Qu├ón and Tien gagged and tied to a tree and another of Ng with his back to the audience while clipping his pubic hair ŌĆō and rumour. ŌĆśInstead of privileging the document, these works become art history through oral transmission,ŌĆÖ Taylor observes.

It is precisely this kind of misrepresentation of performance art that is redressed in Cane 2011 by Singaporean artist Loo Zihan, a live performance in which Zihan re-enacted NgŌĆÖs Brother Cane at the Defibrillator Art Space in Chicago (fig.1). According to Taylor, this work not only raised awareness around Brother CaneŌĆÖs conceptual richness (particularly its criticality towards the criminalisation of homosexuality), but also developed ZihanŌĆÖs own interest in historiography and archiving as an artistic practice. Highlighting ZihanŌĆÖs reliance on Ray LangenbachŌĆÖs written account of NgŌĆÖs actions in the staging of Cane, Taylor argues that ZihanŌĆÖs performance represents an attempt to artistically re-collect the fragmented history of Brother Cane.

Probing deeper into the practice of archiving as art, Taylor singles out Singaporean artist Koh Nguang HowŌĆÖs Singapore Art Archive Project (fig.2). Since the 1990s, Koh has systematically researched and amassed documents relating to artistic practices in Singapore (including experimental works produced in The Artists Village) otherwise overlooked by museums and archives. Since 2005, the Singapore Art Archive has been displayed numerous times ŌĆō including at the Singapore Art Biennale in 1999, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in 1999 and the Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art in 2014ŌĆō15 ŌĆō as a work of art. Yet, despite the demonstrable appetite for the collection, Singapore Art Archive Project has not yet been acquisitioned by an archive. According to Taylor, the failure to acquisition the collection is due to its inseparability from the artistŌĆÖs ŌĆśperformanceŌĆÖ in the form of talks, discussions and recollections and, as such, ŌĆśselling the archive would be tantamount to selling KohŌĆÖ. Under TaylorŌĆÖs reading, KohŌĆÖs practice raises important questions around the relationship between the archive, the artist as archivist and performance as a means of presenting history to the public.

Fig.2

Koh Nguang How ŌĆśperformingŌĆÖ his archive at Nanyang Technological UniversityŌĆÖs Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore, October 2014

Drawing a parallel between KohŌĆÖs meticulous accumulation in Singapore Art Archive and ZihanŌĆÖs installation at the Substation Gallery in Singapore, Archiving Cane 2012, which featured performance documentation from Brother Cane and Cane, Taylor highlights the value performance represents as a means of making the archive visible and relevant to contemporary debates. Similar to KohŌĆÖs ŌĆśperformanceŌĆÖ, Archiving Cane also relied on interaction and social engagement: Zihan encouraged members of the artistic community to contribute their own documentation from the two performances as well as invited Josef Ng to participate in a discussion after the staging of Cane. Through their interactive and communicative gestures (including NgŌĆÖs last-minute substitution of himself with the Thai performance artist Michael Shaowanasai in ZihanŌĆÖs post-performance discussion), Taylor argues that these works ŌĆśbridge artists past and present and revive past debatesŌĆÖ.

In the concluding section of her talk, Taylor considers how artists have used artefacts to evoke historical moments. For example, in Danish-Vietnamese artist Danh V┼ŹŌĆÖs work Chandelier 2012, Taylor argues that V┼ŹŌĆÖs deployment of the original chandelier from the Hotel Majestic in Paris where the peace accords ending Vietnam War were signed in 1973, allows the object to articulate a particular historical moment and its present-day legacy. The chandelier is thus rendered a relic, transforming into a cherished object whose significance is defined by public memory and imagination. Taylor expands on this proposition by further suggesting that historical artefacts can also serve as a means of triggering remembrance and reviving lost voices. Taylor supports this by describing two works: V┼ŹŌĆÖs earlier conceptual piece Phung V┼Ź ŌĆō 02.02.1861 2009, in which the artistŌĆÖs father transcribed a letter written by a French missionary in 1861; and Dinh Q. L├¬ŌĆÖs installation presented at Documenta 13 Light and Belief: Voices and Sketches of Life from the Vietnam War 2012, which showcased drawings made by artists on the front line during the Vietnam War. Recalling ZihanŌĆÖs recourse to documentation in his re-performance of Brother Cane, Taylor argues that these works do not employ documents for their own historic value, but to gain a deeper critical perspective on the role of religion and propaganda in the present.

While Taylor does not assert a historical lineage between the emergence of performance art in Vietnam and Singapore, she opens up new avenues for thinking about shared practices and common concerns about performance art across Southeast Asia. The thematic approach of her research gives rise to wider questions around the study of performance art and the challenges faced by researchers in accounting for the mediumŌĆÖs ephemerality and its legacy in the form of public memory and partial documentation. These concerns transcend the national art histories of Vietnam and Singapore and resonate with transnational debates around the artistic and social value of performance art. As the study of Southeast Asian performance art gathers momentum, TaylorŌĆÖs call to be weary of placing ŌĆśaftermath over eventŌĆÖ offers a fruitful starting point for unravelling the fraught relationship between performance art and public memory in Vietnam and Singapore.

Eva Bentcheva is an independent curator and art historian, and Visiting Research Fellow at Tate Research Centre: Asia in 2016.