The world map has shrunk. The social and geopolitical distance between cites has contracted. Although cross-referencing spatial coordinates might tell one story, the ŌĆśneoliberal poetics of networksŌĆÖ reassures us of another.1 As the narrative so often runs, with the ideological and material dominance of globalised capital the relevance of the nation-state has been surpassed. Anointing the age of global social interconnectedness, the organising principle we must now turn to is the transnational. But if this is true, does the nation have a function today? It is as ethereal as the discourse seems to suggest?

Presented within a series of investigations by Tate Research Centre: Asia into transnationalism and artistic practice, the opening gambit of David TehŌĆÖs presentation was to suggest that the move from the national to the transnational was not as effortless as it may seem. What the lens of transnationalism obscures are the immediate and continuing political pressures that the nation-states place on their citizens. How is it possible, within such frames, to comprehend the historical and continuing ŌĆśdemands of the nationŌĆÖ as they are impressed upon the students, artists and critics constitutive of a nationally-delineated culture?

As Teh claims, the last half-century seems to have evidenced that in the case of Southeast Asia countries, where ŌĆśnationalism has been and continues to be the preeminent mode of political identification and reflectionŌĆÖ, these demands make themselves acutely known. Far from being redundant, Teh claims,

any critical articulation of this trans- must attend, first, to the national and to the international. That a history of contemporary art must, in other words, be both a history of that transnational interchange and a history of what it has meant in given times and places to be international.

Accepting the relative truth of transnationalism but rejecting certain claims to national redundancy, TehŌĆÖs presentation asked to the limits and borders of transnationalism, how, it could be phrased, might contemporary artŌĆÖs transnationalism be mediated through discrete national units? And how might national demands be understood and themselves critiqued (not recovered) within a transnational framework? To attempt to develop this, Teh argues, contemporary Thai art provides an interesting test case for several reasons:

not only is it a place where nation has been preponderant ░┌ŌĆ”] in theory and in practice, in the institution and the conceptualisation of modern art since the 1930s. But also, because its contemporary artists have been, by non-Western standards certainly and especially by Southeast Asian ones, uncommonly mobile and successful in transnational circulation.

It is to the particular national determinations of Thai art as they are bound up in a history and aesthetics of artistŌĆÖs international mobility and distance that such limits can be comprehended. These terms are not simply furnished by practical, spatial and economic qualifications, nor simply in search of an expanded audience, capital and recognition. Mobility and distance, through TehŌĆÖs lens, must also be read along thematic and discursive lines; such terms and the position they are accorded today must be recognised as historically, politically and culturally inflected:

For Thai artists [although, as was subsequently pointed out, this figure is a markedly and admittedly gendered and classed one ŌĆō LH], ways of being and feeling mobile and international, or exploiting distance, far from indicating a global, nomadic subjectivity, are on the contrary closely circumscribed by their national experience and cultural inheritance.

Moving in parallel to the third chapter of his recent book, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (2017), TehŌĆÖs presentation was broken down into three sections. The first, ŌĆśRoundtrips: Mobility and Artistic FormationŌĆÖ sought to define the contrasting modernist and contemporary models of artistic mobility. The second, ŌĆśNirat: Homesickness as a Spatial and Cultural LogicŌĆÖ, attempted to trace a culturally-specific concept of distance and mobility as prefigured in nineteenth-century Siamese culture. The third, ŌĆśCurrencies of Distance in Thai Contemporary ArtŌĆÖ, concluded by considering the role distance plays in Thai contemporary art. While distance and mobility are, as Teh terms it, an ŌĆśartistic currencyŌĆÖ typically figured through reference to globalised conditions, perhaps the central thesis that this paper argued for was that they are equally conditioned by local and national histories.

*

If contemporary art has entered into an irreversible period of international circulation, it was the events of 1989 that marked this threshold ŌĆō including, most obviously, the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the Eastern European uprisings and early signs that the Warsaw Pact was set to dissolve, the Tiananmen Square protests and the seeming ideological ŌĆśtriumphŌĆÖ of capital. Since that point, many of the political flashpoints and their theoretical interpretations have been framed by themes of ŌĆśglobalisation, ░┌ŌĆ”] rapid urbanisation, the neoliberal poetics of networks and, above all, the prodigious mobility of labour, ideas and capitalŌĆÖ. Contemporary art has, in turn, been perceived to occupy a privileged spot within this interconnectedness, with the artistŌĆÖs nomadic mobility figured as the instance par excellence. But, as Teh argues, this familiar narrative of the historically-mediated conditions of artŌĆÖs global circulation, must also be inflected with a historically-, culturally- and geographically-mediated understanding of mobility itself.

As Teh claims, the first instance of mobility to enter into professionalised Siamese visual art comes with the figure of the Italian sculptor Corrado Feroci and the forming of the rongrien praneetsilpakam (School of Fine Arts, Bangkok now known as Silpakorn University) in 1933 ŌĆō an event that operates in tandem with and in the wake of the 1932 Siamese revolution and the overturning of its system of absolute monarchy. As FerociŌĆÖs first cohort of students function to demonstrate, international travel, study and exposure became an ever-more constitutive feature of artistic professionalization. What they signalled were the marks of national and classed distinction.

As the conditions of mobility proliferated throughout the mid-twentieth century, it was Inson Wongsam, a student of Feroci, who emerged as the ŌĆśarch adventurer modernistŌĆÖ. In 1962, Inson undertook his quasi-mythologised journey: travelling via and exhibiting in Dehli, Kerrarchi, Tehran, Istanbul and Vienna, studying at the ├ēcole nationale sup├®rieure des Arts D├®coratifs, Paris and then crossing the Atlantic to go to the US before returning to Thailand in 1974. What ultimately characterises and defines this journey is that its professional and terminal destination was, in effect, his starting point. As Teh terms it, his journey was a ŌĆśround tripŌĆÖ.

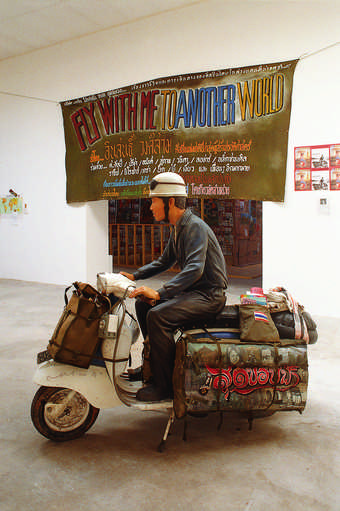

Navin Rawanchaikul

Fly with Me to Another World 1999ŌĆō2009

Mixed media; installation view at Le Consortium, Dijon, 2000

Courtesy of the artist

Loud, tributary echoes of InsonŌĆÖs trip show up most strikingly in Fly with Me to Another World, begun in 1999, a multi-faceted project by Punjabi-Thai artist and Chiang Mai Social Installation (CMSI) co-organiser Navin Rawanchaikul. With its range of materials and outputs, including symposia, publications, exhibitions and pilgrimage, Fly with Me to Another World delved into InsonŌĆÖs life story (not his works) to narrate a tale of national artistic veneration. By contrasting InsonŌĆÖs journey with NavinŌĆÖs contemporary depiction of it, Teh indicates, a signal can be found that points towards a key shift in the patterns and conceptualisation of mobility and distance. Where InsonŌĆÖs ŌĆśroundtripŌĆÖ was in many ways marked out as a return to Thailand, NavinŌĆÖs is, by contrast, a ŌĆśshuttling orbitalŌĆÖ. ŌĆśThe currency of distance had evolved.ŌĆÖ

The first Thai artist Teh identifies to have worked within this circulatory model was Montien Boonma. After studying in Paris, he took a teaching position at Chiang Mai University (CMU) in 1989. Linked to Navin as an ajaan of CMU and the ŌĆśdriving forceŌĆÖ behind CMSI,2 Montien was one of the first Thai artists to achieve significant international recognition. Having exhibited extensively on several international platforms in the early 1990s, his rhythm set the pace. ŌĆśFor those that followedŌĆÖ, Teh proposes, ŌĆśsustained itinerancy became the normŌĆÖ.

Distance, then, had transformed from mark of distinction to condition of professional necessity; as Teh notes, the ŌĆśmost successful [Thai artists] have been the most mobileŌĆÖ. Within this model, the generational shift that begins to occur turns away from the national and towards the international as the primary index for professional accreditation. But what this shift signifies for distance and mobility must also be read within the historic context of pre-modern Siamese cultural forms. Deploying Thongchai WinichakulŌĆÖs arguments in Siam Mapped (1988), Teh contends that it is only in light of Siamese historic understanding of space that the significance of the specific cultural logic of the universal concept of distance becomes fully intelligible.

Via a short detour through traditional, narrative Siamese cartography, it is in the field of literature in general, and the nirat in particular, that Teh settles. As a singular and informative precursor, the nirat is an early-modern form of Siamese poetry that merges the love poem with the long-form travelogue. Forged out of an entrenching capitalist grip on Siam and accompanied by an emerging bourgeois demand for non-courtly, descriptive literature, the nirat emerges as the ŌĆśdefining genre of a new era of mobilityŌĆÖ. This mobility, however, was neither that of the colonial adventurer nor imperial explorer. What in many ways characterises the nirat, Teh indicates, is that the subject penning it and the themes underpinning it are that of the ŌĆśmisery of the homesick travellerŌĆÖ. The poets yearn and mourn. Shot through with the promise of return, the nirat is addressed neither scholar nor court, but to their absent and ŌĆśdistant loverŌĆÖ.

Writing in the early- to mid- nineteenth century, Sunthorn Phu occupies one of the most prominent positions in history of the niratŌĆÖs development. What is here significant about Sunthorn, Teh argues, is that his poems beat to the drum of the burgeoning bourgeoisie. In its contents and its cadence, SunthornŌĆÖs work traces the historical shifts in social structures that Siam was experiencing. In distinction from court literature, constituted by ŌĆśarcane literature and foreign vocabularyŌĆÖ and concerned with ŌĆśthe celestial sphere and royal eulogiesŌĆÖ, SunthornŌĆÖs work was predicated on the aspiration and demands of a non-courtly language and thematics.

Citing the contemporary scholarship of Rosalind Morris, Teh advances that such poetry tracked the socio-ontological constitution of an emerging Siamese subjectivity and their transformed relationship to distance and separation. That is, situated ŌĆśbetween protagonist and narratorŌĆÖ, the niratŌĆÖs authors give the concepts of distance and separation a modern, spatial inflection. ŌĆśThe nirat is born of a temporary displacementŌĆÖ. The authorŌĆÖs movement ŌĆśdirected, inexorable and always with a view to returnŌĆÖ. In essence, a roundtrip.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

untitled (passport no. 1) 2005

Sculpture: paper, hand-drawn facsimile of Rirkrit TiravanijaŌĆÖs passport

Installation view at Serpentine Gallery, London, 2005

Courtesy Gavin BrownŌĆÖs Enterprise

┬® Rirkrit Tiravanija

Photo: Ellen Page Wilson

With passing reference to Kamin Lertchaiprasert, it is to Rirkrit Tiravanija that Teh turns for an indication of an attuned redefinition of professional itinerancy and the idiom of homesickness. As with Navin, it is here not the roundtrip but the subtle ŌĆśorbitalŌĆÖ movement that defines the function of and relation to distance co-constituting his artistic practice. RikritŌĆÖs biography can be coloured by nothing other than international diplomacy: born in Argentina Rikrit was raised in Thailand, Malaysia and Ethiopia before settling and making an artistic career in North America. Based across New York, Berlin, Bangkok and Chiang Mai, in the years running from 1994 to 2004 Rikrit produced no less than 60 solo exhibitions in 14 countries, and participated in no less than 16 biennales in 12 countries. Although lacking the yearning sentimentality typically characteristic of a nirat, Teh outlines, it is RikritŌĆÖs transpositions of his New York apartment ŌĆō such as Untitled, (Tomorrow is Another Day) 1996 and Untitled, (Tomorrow Can Shut Up and Go Away) 1999ŌĆō that appear to have escaped the homesickness that may define why he appears so mythic to a younger generation of Thai artists. ŌĆśBut the formal operation is unmistakable: a literal projection of home onto the foreign landscapes of an orbital itineraryŌĆÖ.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

dogfahr nai meu marn (Mysterious Object at Noon) 2000

Black-and-white 16 mm film, sound, 83 min

Still from the digitally restored version

Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films, Austrian Film Museum and The Film Foundation

If distance operates at the level of narrative, then international circulation hovers at the level of professionalisation. Although this turns up in the work of two prominent artists ŌĆō Pratchaya PhinthongŌĆÖs exhibition ŌĆśMissing ObjectsŌĆÖ at the Chulalongkorn University Art Center 2005 and Arin RungjangŌĆÖs work Russamee Rungjang 2009 or Unequal Exchange: No Exchange Can Be Unequal2011 ŌĆō it is with one figure, perhaps even the figure, that this is most evident: Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Indeed, Apichatpong may be the case in point for arguing, Teh suggests, that ŌĆś[global] mobility might give national belonging a new currencyŌĆÖ. Despite his quick adoption by international cultural scene ŌĆō having studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), gained substantial recognition at the Cannes Film Festival and exhibited on major platforms such as Documenta, the Istanbul, Liverpool, Sharjah and Sydney biennials, to name but a few ŌĆō ApichatpongŌĆÖs recent (not early) practice is ŌĆśuncommonly rooted in ThailandŌĆÖ. The most compelling argument for this thesis is shown in the objects and structures of ApichatpongŌĆÖs films. Somewhat notably, epistolary distance is at the centre of his 1994 work 0116643225059 and the short film A Letter to Uncle Boonmee 2009. Also present in works such as Unknown Forces 2007 and Mobile Men 2008 is the classed and racialised motif of Thai transport workers, users and their infrastructures. The subjects of these works are ŌĆśthe mobile men and women at the barricades in the political standoffs that followed the armyŌĆÖs overthrow of populist premier Thaksin Shinawatra in 2006ŌĆÖ. But perhaps the most singular example of these concerns are found in his feature-length film Mysterious Object at Noon (2000) ŌĆō developed out of his MFA thesis at SAIC. Teh contends that in using his ŌĆśdistinctive, psychogeographic approachŌĆÖ, and although this work oscillates between documentary and fiction and resists the three pillars of Thai cultural heritage (nation, institutional Buddhism and monarchy), it nevertheless remains within realm of the nirat. Not unlike Sunthorn Phu, what Apichatpong hopes to trace in this work is the shifting class structure, notating the rhythm of those workers forced to occupy the marginalised base of capitalist society. Unlike Sunthorn Phu, Apichatpong does not dismiss the working-class country folk he encounters, but casts them as the protagonists of his films.

Teh concluded the presentation by arguing that as the grip of institutes of the artistic modern diminish, contemporary Thai artists have turned ŌĆśto the peripheries for counter-hegemonic resourcesŌĆÖ. As Apichatpong serves to demonstrate, the materials upon which this is built are the tales of the buried, transient or marginalised lumpenproletariat. The tool of narration, aside from symbolism or representation, enables these worksŌĆÖ critical dimension in the post-1989 age of global social interconnectedness. For although ŌĆśthe nirat predates the world-view called ŌĆ£nationalŌĆØ, itŌĆÖs perhaps precisely this pre-national dimension that has made it such a fertile model for contemporary global artistsŌĆÖ. To the globalised demands of capital and Western modernity, Thailand has often presented uncomfortable resistance. Thai conceptions of space, distance and mobility are one key instance of this. Within the history of cultural forms, the ŌĆścontemporary nirat refreshes the ambivalence of narrative and frustrates the supposed universality of modernityŌĆÖ.

A full recording of this event is available upon request. Click to email for further details.