Fig.1

Lynn Hershman

RobertaŌĆÖs Body Language Chart 1978; printed 2009

┬® Lynn Hershman

Performativity, a key term in linguistic philosophy, is used here to describe artworks in which an element is performed or in which the user somehow acts as a performer. Performance, on the other hand, may embrace painting, sculpture, movement, the creation of personae or roles, the staging of events and production of experiences.

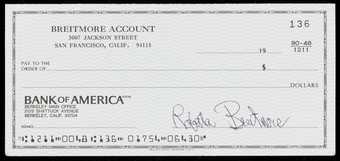

Such works have generated a wide range of documents, including films, photographs, texts from programmes, artist statements, and correspondence. In recent years, these works and their documentations have radically challenged practices of curation, exhibition and preservation of art by shifting the focus from the object to the process behind and around it. Lynn HershmanŌĆÖs RobertaŌĆÖs Body Language Chart 1978 (fig.1), for example, offers detailed instructions about the creation of ŌĆśŌĆÖ, a fictional role that was created, performed and documented by the artist for a period of four years between 1974 and 1978. Roberta, who could be described as a semi-autobiographical persona, was met primarily and now exclusively, in the ŌĆśŌĆÖ captured over the four years of its ŌĆślifeŌĆÖ. This poses the question of where does the documentation of this work reside? Is it in what was photographed or written about it at the time by the artist (fig.2), in what was subsequently released, in the fleeting appearance of a Roberta-look-alike robot in Hershman LeesonŌĆÖs Second Life replay 2007, in the documents stored at Stanford University Library, or those still outside the public eye, kept in Hershman LeesonŌĆÖs own studio, or in Professor Kristine StilesŌĆÖs memory of what occurred at the time of her own performance of a multiple of Roberta in 1976? To put the same question differently, what document captures the work best? Is it the well-known Roberta Construction Charts, the Transformation Charts, the advert placed in a local paper in which Roberta sought a companion, records of meetings, a psychiatric assessment, a driverŌĆÖs license, a cheque from the Bank of America (fig.3), an anecdote told by the artist over dinner over forty years after Roberta came to ŌĆślifeŌĆÖ? Or is it possible that the performance is, in fact, the result, invariably changing over time, of an intermedial network comprising live events, historic documents, secondary documents, their replays, and more or less subjective memories and associated oral histories? If so, how can we evaluate when the documentation of a performance starts and ends? How can a scholar or a museum assess which elements of a performance need to be documented and preserved, or even whether these documentations may at some point become works of art in their own right, requiring further documentation and a different type of preservation? If in performance studies and, to a lesser extent, in new media studies, scholars, provokingly perhaps, leave these questions unanswered, in museums practices developed for the documentation and preservation of objects now need to be revisited to capture the genesis of processes, the occurrence of live events, their changing reception, and their curation and preservation over time.

Seminal publications in performance studies have addressed documentation and come to very diverse conclusions. These include Peggy Phelan, ŌĆśThe Ontology of Performance: Representation Without ReproductionŌĆÖ, in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London 1993), which focuses on the non-reproducibility of performance. For her, performance cannot be ŌĆśsaved, recorded or documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representationsŌĆÖ.1 Amelia JonesŌĆÖs ŌĆśŌĆÖ (Art Journal, vol.56, no.4, 1997) and her recent Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art and History (Abingdon and New York 2012), on the other hand, stress the importance of the role of ŌĆśperformative documentsŌĆÖ in securing the role of the artist. PhelanŌĆÖs position is often cited to be in opposition to that of Philip AuslanderŌĆÖs ŌĆśŌĆÖ (PAJ, no.84, 2006) in which he suggests that there are in fact two types of documentation: the documentary, proving that a performance occurred, and the theatrical, is a form of ŌĆśperformed photographyŌĆÖ which sees performances staged solely to be photographed. For him the crucial relationship is therefore not so much between performance and its documentation as between documentation and its audience. Building on this, Rebecca SchneiderŌĆÖs Performance Remains (London 2012) suggests that the archive, where performance, as the title suggests, persists in time, should be considered as a performative place, while Barbara ClausenŌĆÖs performance and lecture series ŌĆśAfter the Act: The (Re)Presentation of Performance ArtŌĆÖ and ŌĆśWieder und Wider: Performance AppropriatedŌĆÖ at the Museum of Modern Art Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna, together with the associated publication After the Act: The (Re)Presentation of Performance Art (Vienna 2007), suggest that the interest in performance art should not begin with or end with the ŌĆśauthentic experienceŌĆÖ, but rather that it should be seen as ŌĆśan ongoing process of an interdependent relationship between event, medialisation, and receptionŌĆÖ.2 Crucially, Clausen shifts the attention from the live event to its mediation and transmission. The question of transmission and, especially, replay raises questions over ethics, as discussed in Claire BishopŌĆÖs ŌĆśŌĆÖ (October, no.140, 2012) and the essay by Heike Roms and Rebecca Edwards, ŌĆśArchiving Legacies: Who Cares for Performance RemainsŌĆÖ in Gunhild Borgreen and Rune GadeŌĆÖs Performing Archives/Archives of Performance (Copenhagen 2013). On the other hand, Richard Rinehart and Jon IppolitoŌĆÖs Recollection (Cambridge, MA 2014), focusing on new media preservation, point out the ephemerality of media, and their ability to be preserved, and thereby unwittingly draw our attention back to PhelanŌĆÖs writings about performance and ephemerality.

Partly in response to the growing significance of performance documentation in the museological context, and the burgeoning debate in performance and new media studies, Tate initiated a number of projects on performance and documentation. These include the AHRC-funded network on ŌĆśAuthenticity and PerformativityŌĆÖ (2009ŌĆō10), which investigated the importance of performativity as a parameter of new media art; the internally-resourced programme ŌĆśPerformance and PerformativityŌĆÖ (2011ŌĆō12), which aimed to broaden ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs understanding of performance and performativity through a number of events involving artists, museum professionals and academics from art history, sociology, cultural theory, education, theatre and performance; and the AHRC-funded ŌĆśCollecting the PerformativeŌĆÖ project (2012ŌĆō13), which looked at emerging practices relating to the collection and care of performance art. This latter was particularly influential on ŌĆśPerformance at TateŌĆÖ in determining the need for a thorough investigation of how museums should document, preserve and share performance after the live event.

Funded by the AHRC, and building on the findings of the above research at Tate, the two-year project ŌĆśPerformance at TateŌĆÖ aims to research, document and make public the history of performance at Tate from the 1960s to today, identifying the challenges in determining what it means to document performance in the museological context. The project will create a chronology and outline the history of performance at Tate while also exploring the neglected histories of the performative aspects of many modern and contemporary artworks in the collection. Additionally, the project will research how this history has influenced museological and curatorial practices of documentation at Tate and beyond, and how it relates to past and current debates about this burgeoning field. In parallel, Collaborative Doctoral Researcher Acatia Finbow will research the uses of and potential values of secondary documentation for curators and audiences.

As well as being in dialogue with ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs past investigations into performance and performativity, ŌĆśPerformance at TateŌĆÖ aims to advance knowledge in terms of the capture and documentation of the user experience by building on findings by projects such as the AHRC-funded ŌĆśŌĆÖ (2004ŌĆō9), which researched what constitutes presence in live, mediated and simulated environments; the RCUK-funded ŌĆśThe Documentation and Archiving of Pervasive ExperiencesŌĆÖ Horizon project (2011), which developed a documentation and archiving tool called CloudPad that used cloud computing for the synchronous documentation of mixed media resources; and the RCUK-funded ŌĆśArtMapsŌĆÖ project (2012), which generated a web-based application through which artworks from ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs collection can be encountered and annotated outside of the museum. Findings from the AHRC-funded projects ŌĆśŌĆØŌĆÖ (2009ŌĆō11), and the ŌĆśŌĆÖ project (2011ŌĆō13), investigating the replay of archival materials through practice-research and focusing on reception, have helped shape this burgeoning field, which increasingly recognises documentation as an area which deserves renewed attention. Work by ŌĆśDocumentation and Conservation of the Media Arts HeritageŌĆÖ () at Langlois Foundation and at V2 have shaped the field on relation to new media art, and ŌĆśPerformance at TateŌĆÖ will build on such initiatives while also, distinctively, attempting to write a history of documentation.

ŌĆśPerformance at TateŌĆÖ aims to build on these debates by looking at performance documentation as a generative tool, a field of production and interpretation that is less significant in terms of its ontological relationship to performance and more interesting for its phenomenological and epistemological roles. The project will generate a scholarly online publication analysing the history of performance at Tate through 100 case studies covering the period from 1960 to today. Accompanying essays will explore different aspects of performance with reference to ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs collection and engagement with performance. The project will also capture, document and replay user experiences of performance at Tate, using the Mus├®e de la DanseŌĆÖs two-day transformation of ╔½┐ž┤½├Į in May 2015 as a case study. Finally, the project will explore novel ways to display the performative aspects of work in the collection. Project outcomes will include an edited book, articles, conference papers, and an international conference to be hosted at Tate in 2016.