As part of my graduate internship with New York University in 2021 to 2022, I worked on access to artist CD-ROMs with Collection Care Research at Tate. Keith PiperŌĆÖs project Relocating the Remains 1999 served as a case study to explore the technical aspects of how to enable interaction with the CD-ROM contents. I also paid attention to maintaining essential characteristics like colour, and behaviours like click reaction times or rollover animations, which can be affected by current methods of access. My research also considered where artist CD-ROMs sit within ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs collections and how that affects discoverability and access, as well as available preservation resources.

Artist CD-ROMs

To understand how revolutionary CD-ROMs were in the 1990s, letŌĆÖs set the scene: the first personal computers had only been around for a few years and graphical user interfaces with a mouse were still a recent development. The World Wide Web did not yet exist for the general public. The only moving image content came from television and movies (either the homemade kind, on VHS, or from major production companies), but they could not be watched on your computer because it had enough trouble just running word processing software.

Then along came a few game-changing developments that enabled the explosion of CD-ROMS. Software like MacroMind Director was released, which could create interactive digital animations. ISO 9660, a digital format standard, was expanded to support the type of multimedia content being created and to be readable on both PC and Macintosh systems.1 And CD-R optical discs, which held almost 500x more data than a standard floppy disk, became widely available at an affordable price point. With these elements in place, it became possible for many more people to create media content and distribute it.

This new creative medium, called multimedia or interactive digital media, was appealing to artists as an expressive tool with more possibilities than anything else up to that point. Some established artists like Laurie Anderson and Antoni Muntadas made CD-ROM projects, and many new artists were drawn in by what digital media had to offer. The opportunity to work creatively with interaction, images, animations and sound on a new platform, the home computer, was empowering and exciting. It seemed that a whole new world was being birthed, and the creators were making it into whatever they wanted it to be.2

Publishers also saw great potential in the CD-ROM format as a distribution platform because it could sit alongside print production as a mass medium. Many CD-ROMs were added to printed formats like books as supplemental material that extended the content and provided an incentive for consumers. This type of partnership sent multimedia art directly to viewers and supported a wider audience than galleries alone could.

CD-ROMs enjoyed time in the spotlight in the 1990s and early 2000s, with artists sharing their latest projects at digital arts festivals like . Some galleries expanded their offerings to include works on CD-ROM and sold them in editions, and curators who championed digital media as an emerging field included these works in exhibitions. The 1996 exhibition Burning the Interface in Australia and (1999ŌĆō2001) were entirely composed of CD-ROM works that visitors could interact with on computers in the galleries.

Contact Zones showed the work of over 90 artists, including Keith Piper, whose CD-ROM work Relocating the Remains is a case study for this research project. The exhibition travelled to three locations in the USA, in addition to Canada, Mexico and France. The sense of possibility around CD-ROMs was captured by Contact ZonesŌĆÖ curator, Timothy Murray:

A wealth of opportunity for cultural exchange and conceptual reflection has been catalysed by recent developments in digital art. Practices of artistic appropriation, collage, and montage have been heightened by digital possibilities of overlapping, juxtaposing, and morphing complex sequences from visual and aural history. What previously could be considered in only one frame or screening can now be analysed on simultaneous platforms and from multiple perspectives, both locally and globally.3

MurrayŌĆÖs comments articulate how technologies of exchange opened up a new sense of connectivity and engagement within visual culture. The interpretations of narrative construction and meaning-making supported by CD-ROMs initiated a massive shift from the linear context of film and video to a more open, networked context. The relative ease of bringing together content from multiple media sources, making them interactive and sharing them across geographies and social spheres enabled both creators and consumers of digital media to develop ideas in new ways with new influences.

This set the stage for the World Wide Web, which fulfilled many of the functions that CD-ROMs supported, without the strict data capacity of optical discs or their need to be physically sent around for viewing. The even newer set of possibilities afforded by browsers, code and connected communities on the Web gathered momentum alongside CD-ROMs in the 1990s, eventually superseding them.4

TodayŌĆÖs challenges for CD-ROMs

Although CD-ROMs can be traced as a major root of digital art history, these projects are still not very present in exhibitions of digital art. There are several reasons for this. Many CD-ROMs have ended up in libraries because of their inclusion with published books, but they did not fit well into existing cataloguing or storage systems, which struggled to accommodate non-print media. Depending on the library, it can be a bit confusing to search for CD-ROMs and request access to them. In some cases, the CD-ROM disc might be missing or damaged. Some CD-ROMs were only distributed by artists or had very limited production, so they may only be held in personal collections, if they were saved at all.

Fig.1

An optical disc drive for a computer

Even when those obstacles can be overcome and a CD-ROM is available, it is unlikely that a computer will support it today. Firstly, an optical disc drive (fig.1) is needed to read information from the CD-ROM. In the mid-2010s major computer companies stopped including disc drives. This was both to save space in a competitive market where thinner and lighter portable computers were the trend, and in response to the rise of portable USB drives and cloud services like Dropbox to store and move digital files around. Secondly, the CD-ROM content is unlikely to be compatible with the operating systems on current computers, such as Windows 10 or macOS Monterey. Trying to open a CD-ROM program would likely result in a warning that it cannot be run. You might think that installing a compatible operating system on the computer would solve the problem ŌĆō and it might, if that were possible. However, the underlying architecture of current computers (especially Macs) just does not work with older operating systems; an analogy is trying to run a train on tracks that are not the right size. Does this mean we have hit a dead end for artist CD-ROMs, and their contents are lost to time and technological progress? Not necessarily so.

Legacy computers

Fig.2

An Apple eMac, a legacy computer from 2002

One strategy to access CD-ROM content and other obsolete digital formats is to maintain older computers and software, sometimes referred to as legacy computers (fig.2). For CD-ROMs, these would be Macs or PCs from the mid- to late-1990s and early 2000s, running something like Mac OS 9 or OS X, or Windows 2000 or XP. Using legacy computers has the added benefit of presenting the content in its native environment, where things like display type and resolution, system sounds, and even the keyboard and mouse designs can affect the experience of the content. For an art historical researcher, these aspects can be an important part of trying to understand what an interactive piece was like when it was made, or why an artist programmed the piece in a certain way.

Although they can be a powerful tool for accessing CD-ROM content, legacy computers are not always a perfect solution. They can be hard to come by, depending on how old they are and how available they were to begin with. And, of course, they cannot be expected to work forever. We have all experienced a buggy old computer that crashes, has sticky keys or just does not turn on one day. As time goes on, it becomes harder to procure working legacy computers that fulfil the needs of supporting access to CD-ROM content.

Before looking at other solutions, it might be helpful to return to our train analogy. Say that the train is the CD-ROM content and the computer system is the tracks. Generally speaking, we would not want to change the train to fit the tracks; changing the artistŌĆÖs work to fit the computer system would not only potentially damage the authenticity of the work in the eyes of users and historians, but it could also violate the artistŌĆÖs copyright. Thankfully, there are some tools that help us adapt the train to different tracks so that everything can work without running afoul.

Virtual machines and emulators

If we want to run the original train (the CD-ROM content) on different tracks (a current computer), there are specialised tools to help us do that: a virtual machine (VM) or an emulator. These tools allow a current computer to act as a host to run older operating systems like Mac OS 9 or Windows 2000. The VM or emulator are like adaptors that fit these otherwise incompatible pieces together. Although technically speaking they do this job in different ways, for our purposes they have the same effect of providing a way to access the contents of CD-ROMs on current computers.

The CD-ROM content might be read from the original disc if the VM or emulator can recognise an optical drive (instead of built-in drives, an external USB drive can be used). When that is not the case, the CD-ROM content has to be transferred to a digital file format called a disk image. A disk image is a one-to-one copy of the entire contents down to the bit level (the 0s and 1s that the computer actually works with). It can be thought of as a virtual clone of a CD-ROM, which is a different process than simply copying all the files you see. The disk image provides access to the CD-ROM contents in a VM or emulator, with the added benefit that it is a more sustainable, archival copy of the information. The disk image format itself is less dependent on hardware and software to access its contents, and as a digital format it is not at risk of physical degradation or damage like the CD-ROM disc.5

Some VMs and emulators are not that difficult to set up, and some CD-ROMs run well on them. However, the more complex a CD-ROM project is, or if very specific software or plugins are needed, the content might not work correctly ŌĆō or it might not run at all. While this can certainly be annoying, it is also a concern regarding the integrity of the artwork. If a CD-ROM is supposed to be in full-spectrum colour but it only displays in greyscale, or if animations are supposed to play when the mouse arrow hovers over a certain area but it is not working, that means it is not a faithful rendering of the artwork and we are not able to understand it correctly. In our analogy, the tools we are using are not doing a very good job of fitting the train to the tracks, and we are in trouble.

There has been some research done to establish how libraries and other collections can provide access to CD-ROMs, and to ensure that the integrity of the contents can be maintained. For libraries, archives, and other collections a large quantity of optical discs might be part of the challenge. Firstly, it is not always clear what kind of material is on the discs ŌĆō several varieties of optical disc look alike, and could contain music, movies, interactive content, personal or work files, and pretty much any other kind of data that existed when the disc was made. There are different ways to transfer these materials to a disk image, and it takes time to inspect each optical disc and choose the correct method. Secondly, even if the correct method is used, it is possible that interactive content will not work. For example, in the course of this research project I found that a certain version of QuickTime software was required to support features of the CD-ROM content. Other software and plugins from the 1990s and early 2000s can be necessary, and they can be hard to track down. In some cases the VM or emulator is not compatible with them, or it does not support a particular function such as microphone input that activates the work on the CD-ROM. These kinds of problems are not apparent without testing in the appropriate operating system and software environment, which takes even more time and resources. All in all, these conditions can be yet another obstacle to accessing CD-ROM contents and they cannot be resolved with a well-constructed workflow alone.

A third issue for stewards of CD-ROMs is that procuring and using copies of older operating systems and software that are licensed falls into a legal grey area. While the companies, such as Apple or Adobe, may no longer have the technical or staff infrastructure to provide and validate licenses for their products, that does not translate to a free pass for anyone to use them. Further, preservation often involves creating copies in order to safely back up information, and to provide access to researchers and other users. Such reproduction is often prohibited, which widens the legal grey area. Organisations like the have done valuable work in the areas of law and policy and developing fair use guidelines, but it is still in progress.

Migration or reconstruction

When older equipment and software are not available, and when VMs or emulators do not allow CD-ROM content to run properly, a third option is to migrate the content to a different format that is compatible with available equipment and software. In our trusty analogy, this is like rebuilding the train with as many existing parts as possible, but making its wheels meet the tracks.

For media artworks, migrating the content means transferring it or reconstructing it in a technology or technologies that will reproduce its functions and aesthetics faithfully while allowing it to run on current equipment. An added benefit is that the new format is often more sustainable. One example of migration is transferring the contents of a VHS tape to a digital file; we can still watch the video, but we no longer have to find a VHS player or worry about the tape degrading. It is also much easier to create backup copies of the video for safekeeping, or to make other versions of the digital file for different playback systems.

Migrating CD-ROM content can be a big undertaking because so many different kinds of behaviours and media types are involved. The technologies needed might not be especially sustainable, so the issues would have to be addressed again before too long. It can also be debated that reconstructing the content in another medium is not appropriate for a particular artwork because the CD-ROM format or its underlying code, or even the software that was used to create it, are important conceptual or historical elements that should not be lost. All of these reasons mean that migration is not taken lightly and it has not been a popular solution for CD-ROMs to date.

Train maintenance

We have covered a lot of ground in addressing the potential issues that stand in the way of experiencing artist CD-ROMs, but there is one last important detail, which is how all of this work might be accomplished within a collecting institution where CD-ROMs are held. Who is maintaining this train system?

As we have learned, it can take a lot of technological resources and expertise to enable access to CD-ROMs. In a library or archive setting, it can be hard to support the preservation and access of CD-ROMs because staff are not necessarily trained in these processes. It also involves a budget for computers and software, digital storage for disk image files, and perhaps hiring a digital preservation specialist to help with the work. These costs add up and can keep CD-ROM access projects from moving forward. The most common approach to access that I encountered during my research was to assess preservation needs for a CD-ROM at the time of request. This piecemeal approach can keep time and resource costs low, but often sacrifices a more robust infrastructure that could serve more media content to more people, more often.

One of the most established networks of expertise on CD-ROM access is Rhizome and Emulation-as-a-Service (EaaS). Rhizome is a non-profit digital arts and culture organisation that grew out of the very community it serves, and has undertaken many significant digital preservation projects throughout its history. Dragan Espenschied, Ėķ│¾Š▒│·┤Ū│Š▒ŌĆÖs Preservation Director, has collabourated with EaaS (now or EaaSI) to research, develop and apply methods of on-demand emulation of CD-ROMs.6 The Theresa Duncan CD-ROM project by Rhizome is a good example of what EaaSI can do.7

Ideally, a collection of CD-ROM disk images would be available to a user group (for instance, a libraryŌĆÖs patrons or the public audience of an exhibition) through a normal internet browser, and the EaaS interface would automatically choose an appropriate emulation to view the work. This scenario removes a lot of labour from the moment of access, but it does require a great deal of preparation to make that moment happen.

In reality, at this point, access through EaaSI still requires manual setup of the correct emulation and there can be some problems such as limited simultaneous users (meaning wait time to see the emulation) and slow response times because of delays in internet service, which can be frustrating for interactive content. However, it is a very promising project that supports access to many types of computer-based information like born-digital archives and scientific data sets, in addition to historic digital media artworks.

The multiple challenges to accessing CD-ROM content too often keep these ground-breaking and valuable works out of the public eye. The opportunity to revisit the CD-ROM era and its many exciting experiments in digital media and interaction should be available to anyone interested in them. I hope that with efforts like this research project and the support of collections staff and curators, these conditions might improve.

Case study CD-ROM: Relocating the Remains by Keith Piper

Fig.3

Keith Piper

Relocating the Remains book cover

┬® Iniva and Keith Piper

Fig.4

Keith Piper

Relocating the Remains CD-ROM supplement

┬® Iniva and Keith Piper

Keith PiperŌĆÖs project Relocating the Remains (figs.3ŌĆō4) was used as a case study to test preservation and access methods for CD-ROMs, and to examine its status within the institution as an item with artistic content currently held in ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs library. Piper, a leading figure in contemporary art, was a founding member of the BLK Art Group in the UK. His practice focuses on thematic concerns around race, history and culture, and has taken form in a wide range of media including painting, sculpture, photography, installation, video and computer-based interactivity.

Relocating the Remains was commissioned by Iniva, the Institute of International Visual Arts, and released in 1997 along with a published monograph featuring a major essay by Kobena Mercer on the occasion of a solo exhibition at the Royal College of Art, London that later travelled to the New Museum in New York in 1999.8 Relocating the Remains was also included in the CD-ROM exhibition in 1999.9 The CD-ROM was conceived as a sort of retrospective form of PiperŌĆÖs work since 1981, in which he ŌĆśexplore[d] uses of emerging ŌĆ£interactive technologiesŌĆØ to ŌĆ£revisitŌĆØ work from the 1980s and 1990s in the form of digital facsimiles that could be explored through user browsable devicesŌĆÖ.10

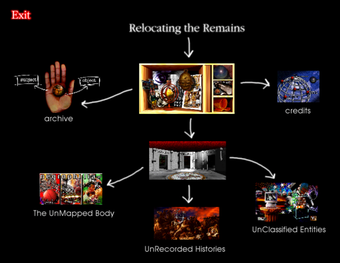

Fig.5

The virtual gallery space on the Relocating the Remains CD-ROM

Its interface design uses a virtual gallery space for users to browse three themed rooms: ŌĆśUnMappedŌĆÖ, ŌĆśUnRecordedŌĆÖ and ŌĆśUnClassifiedŌĆÖ (fig.5). Each virtual room contains an installation with elements of earlier projects, and clicking on them opens sequences of images and/or video that introduce the selected project. As a user moves the mouse around, some elements are activated with audio or animations. More details, such as photographs from previous installations, medium lines, videos, or writing about the piece, can be accessed through links to more content on the CD-ROM (fig.6). Beyond this exhibition-style space, there is an ŌĆśArchiveŌĆÖ section containing an extract from Kobena MercerŌĆÖs monograph text, ŌĆśWitness at the crossroadsŌĆÖ, along with documentation of past projects by Timeline or by Media.

Fig.6

Screenshot of a map of the main contents of the Relocating the Remains CD-ROM

As scholar Gilane Tawadros describes it, ŌĆśPiper allows you to follow a ŌĆ£timelineŌĆØ of his artistic oeuvre except that this ŌĆ£timelineŌĆØ leads you sideways and diagonally, in and out and across time. The artwork acts as an archive of a living past, one through which each viewer navigates their own path.ŌĆÖ11 The lack of prescribed narrative and freedom to follow oneŌĆÖs own curiosity was a hallmark of ŌĆśmultimediaŌĆÖ art, which Piper put to good use for this digital retrospective project.

Piper has also documented Relocating the Remains, in a way, on his own website.12 There is an embedded video of the CD-ROMŌĆÖs intro sequence, and an essay on how it was made and how it subsequently aged in a landscape of changing technologies. In a 2021 interview with Tate curators and conservators, Piper related that in the mid-1990s he thought he was working with technology of the future, but ŌĆśit almost instantaneously became archaicŌĆÖ.13 He described multiple cases where later exhibitions of interactive or programmed digital works experienced issues of obsolescence or misplaced elements that were needed to make the whole system work.

Now, over two decades on, Piper is still engaged with exhibiting his technology-based works and looking to keep the older ones running. He had been involved in a proposed collaboration with , the and at the University of Plymouth to investigate the use of emulation, but plans unravelled during the Covid-19 pandemic. During the 2021 Tate interview, Piper related that institutions are being relied upon to have the capacity and resources to take on properly archiving and stewarding such complex works over time because individual artists like himself cannot take on that responsibility alone.

Technical research and testing

Tate Collection Care Research initiated this project in recognition of the increasing difficulty in accessing and exhibiting CD-ROM content and the risk that they were being overlooked as an important moment in the history of digital art. Part of the challenge lies in the fact that CD-ROMs are mainly held in library collections, where there may not be sufficient resources to take on the work of making them accessible. The Time-based Media Conservation team may have more expertise and equipment, but they have limited capacity as the permanent collection of artworks keeps the staff busy with new acquisitions, exhibitions, and loans.14 To date, there are no CD-ROMs in the permanent art collection at Tate, so there is not an established infrastructure for their care.

My technical research for Relocating the Remains luckily started with a copy of the work itself; other works that were considered, such as Donald RodneyŌĆÖs AUTOICON, were not available due to lending restrictions from special collections in libraries. Because Relocating the Remains is still in publication, it could be purchased and delivered to me in New York, where I conducted my remote placement with Tate.

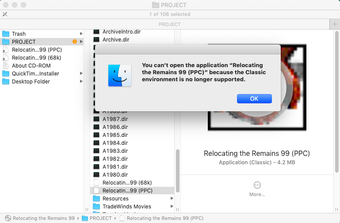

Fig.7

Screenshot showing the result of an attempt to open the Relocating the Remains program on a current Mac computer

The initial steps were guided by trying to understand what is actually on the CD-ROM in the first place. This in itself took some setup, since many of the obstacles discussed above were present in my research environment. I worked with my own Mac laptop, which did not have a built-in optical disc drive, so I used an external USB disc drive. As expected, the program that runs Relocating the Remains was not compatible with my macOS operating system, so I could not look at the artistic content yet. However, I could at least see what files were included on the disc with the Finder (fig.7). This is not always the case, since not all file systems can be successfully read on all operating systems.

CD-ROMs are an interesting format because their underlying architecture can contain multiple file systems and almost any data type. This means they can have programs that run on Windows and Mac on the same disc. The ISO 9660 standard enables this, and it was designed and expanded upon over several years to serve many purposes for users in different computing environments. To understand how flexible the CD-ROM format is, think of a video tape as a counter-example: there is only one kind of information that can be written to the video tape, and the tape can only be ŌĆśreadŌĆÖ by a video deck. By contrast, CD-ROMs can hold audio, video, images, program code, software and many other file types, all to be ŌĆśreadŌĆÖ by either Mac or PC computers.

The ISO 9660 standard was a great benefit to multimedia producers, who could get creative about what type of content went into their CD-ROM projects. And it was great for consumers, who did not need to worry about what kind of computer they had since the CD-ROM they had purchased would work on a Mac or a PC.15 However, in terms of preservation the variety of content can make it challenging to be sure that everything is identified and saved properly. Perhaps there are different versions of files, or even different content entirely, for Mac versus PC on a single disc, and our sometimes limited computer resources for preservation could create gaps in what is saved.

After securing an optical disc drive to access the contents of the CD-ROM, I identified some software tools to look deeper at Relocating the Remains. Most software made for handling optical disc media is built for Windows or Linux, but there are a few for Mac as well. Even though I only have a Mac laptop, I also have access to Windows and Linux on virtual machines, which I can use on my Mac. This enabled me to use a variety of tools to analyse and access the CD-ROM content.16

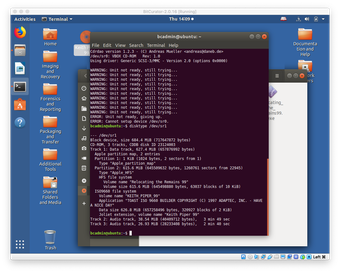

Fig.8

Screenshot of the BitCurator Environment. Running the disktype command in Terminal shows the underlying architecture of the CD-ROM. Relocating the Remains has both Mac and PC file systems, plus 2 audio tracks

The first tool I used was , which is a Linux distribution pre-loaded with a collection of free and open-source digital forensics tools, managed by the BitCurator Consortium (fig.8). I also used VirtualBox to run BitCurator on my Mac laptop.

The disktype command line tool showed me that the Relocating the Remains disc contains 3 tracks. Track 1 is a data track holding the interactive program and its assets. This track has both Mac and PC file systems, which told me that I should be able to run Relocating the Remains on both Mac and PC platforms.17 Tracks 2 and 3 are audio tracks, and can be played on any device that would play CD tracks, like a CD player or a computer.

The ŌĆśHFS file systemŌĆÖ shown with disktype indicated that the Mac-compatible files needed to run on an older operating system that is no longer compatible with current computers. HFS, or Hierarchical File System, is a hard disk format that had full functionality up to Mac OS X 10.5. Starting with macOS 10.15, HFS disks cannot even be read. The names of the program files themselves on the Relocating the Remains CD-ROM also gave clues about what operating systems would run them. The file named ŌĆś(68k)ŌĆÖ was meant to be compatible with Apple Macintosh computers with CPUs from MotorolaŌĆÖs 68k family, which was used up to System 7. The ŌĆś(PPC)ŌĆÖ file was compatible with the next generation of Macintosh computers using PowerPC architecture, which ran System 8, Mac OS 9, and Mac OS X up to version 10.5.

While all of that information might seem like a lot of nerdy trivia, it is important in identifying which operating system would be the most appropriate for viewing the work in an environment that would have been available to viewers in the late 1990s. The obstacles of compatibility issues also narrowed down which operating systems would actually work with the Relocating the Remains program files. And lastly, the choice of operating system determines which emulation software I would choose to set up.

Before using emulators, though, my priority was to run the program on the original CD-ROM so that I could establish a baseline for what should be considered ŌĆśnormalŌĆÖ behaviour, such as colours, sounds, and how quickly interactive elements respond. This is an important aspect of the preservation process, since ideally there should be a reference for the original content in order to compare how well preserved or migrated versions work.

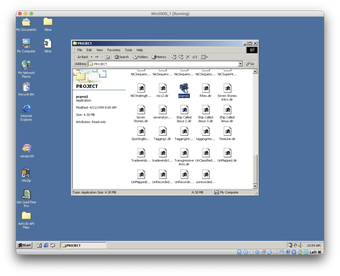

Fig.9

The PC-compatible version of Relocating the Remains was in the ŌĆśProjectŌĆÖ folder and titled ŌĆśpcproj1ŌĆÖ, which made it hard to find

By using Windows 2000 in VirtualBox software, I could run the CD-ROM from the USB optical disc drive and experience the PC version of Relocating the Remains. It was a bit confusing to find the Windows-compatible program on the disc, though ŌĆō it was stored in the ŌĆśProjectŌĆÖ folder, buried in a long list of files, and titled ŌĆśpcproj1ŌĆÖ (fig.9).

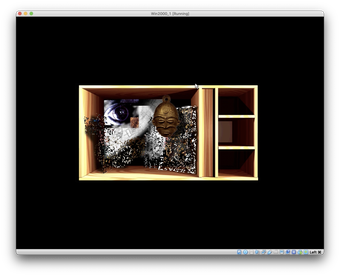

Fig.10

The ŌĆśmain menuŌĆÖ interface of Relocating the Remains fades in as the introductory sequence plays on the PC version, running in a Windows 2000 virtual machine

Once the project was opened, I saw a short introductory sequence with text and graphics fading in and out. A ŌĆśmain menuŌĆÖ interface materialised (fig.10), and I clicked around to get an idea of how this PC version behaved. I created a short screen recording as a reference, so that I or someone else could quickly see some of the content without having to set up the Windows 2000 virtual machine and USB optical disc drive again.18 I would do more exploration of the CD-ROM in this environment later, but I wanted to move on and see if I could experience the Mac version.

In order to run Mac OS 9, which was released in 1999, on my current Mac laptop, I would need to run an emulator. Virtual machine software like VirtualBox is not compatible with the architecture of OS 9, so another solution had to be found. is a well-supported, open-source emulator software that runs Mac OS 9. It takes a bit of setup to download the SheepShaver software itself, locate a version of the Mac OS 9 operating system and a ROM image, but I was able to do so in the course of an afternoon.19

One important distinction with SheepShaver is that it does not recognise actual CD-ROM discs. This meant that I needed to create a virtual copy of the CD-ROM, called a disk image. A disk image is a bit-for-bit clone of the entire information contents of a storage device, including the file system and all of the files in it. This is a different process than simply copying the files using a Finder or Explorer interface (or even the copy functions in a command line utility). A disk image file contains the whole environment needed to successfully run the executable programs found on CD-ROMs.

Disk images can be made with software, or with command line utilities. Some disk imaging software handles the contents differently, and does not always produce a disk image file that works with older Macintosh file systems.20 I used Guymager, which is included in the BitCurator Environment on Linux, Isobuster on Windows, and the dd command-line tool on Mac to make a few disk images to test. These software are the most commonly used and well documented options for digital preservation purposes.21

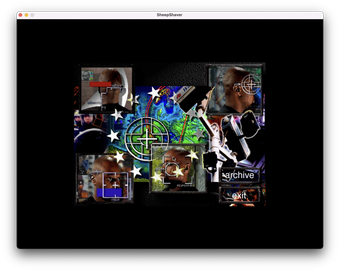

Fig.11

Still image excerpts from the opening sequence only found on the Mac version of Relocating the Remains

Fig.12

The PC version has no interactivity in this section, with only still images and no audio. In the Mac version, the figure spins around and audio clips of archival recordings play as the mouse moves over each portrait.

Fig.13

In the Mac version, the figure spins around and audio clips of archival recordings play as the mouse moves over each portrait.

After creating the disk images of Relocating the Remains, I tested each version in the SheepShaver emulator running Mac OS 9. The first thing I noticed when running the Mac version of the Relocating the Remains program was that there was an entirely different opening sequence (fig.11). A further detail was that the fade-ins involved smaller, coloured squares. Once the ŌĆśmain menuŌĆÖ interface loaded, I was also surprised to find that some of the elements like the astrolabe and glass ball turned when the mouse moved over them (figs.12ŌĆō13).

Most notably, some of the artworks became activated as animations or audio clips in the Mac version but were only still images with no sound in the PC version. The experience of the Mac version was much richer and imparted a deeper understanding of the works being represented on the CD-ROM.

Moving on with the testing, I tried each of the disk images I made to see if there were any difference among them. Thankfully, they all worked in SheepShaver and I did not discover any problems as I navigated through them.

Another emulation platform that I wanted to try was (Emulation as a Service Infrastructure) since has been written about extensively for use with CD-ROMs and is used in Ėķ│¾Š▒│·┤Ū│Š▒ŌĆÖs CD-ROM preservation and access project. The appeal of EaaSI is that many operating systems can be available through a single interface, precluding the need to set up multiple virtual machines and emulators. The downside of EaaSI is that it requires a higher level of IT knowledge, a dedicated server, and administrative responsibilities to manage account-based user access.

When I reached out to EaaSI to inquire about testing the service, they pointed me to New York UniversityŌĆÖs (NYU) library staff, who had set up an EaaSI node and were in the process of vetting it. They very kindly set up a user account for me, so that I could access the platform remotely. Using the Chrome browser, I was able to sign in, upload a disk image file for Relocating the Remains, and test it in various computer operating systems that NYU had set up.

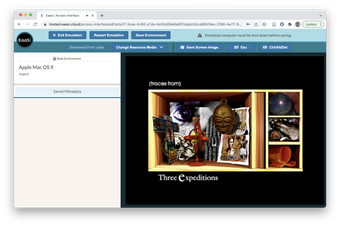

Fig.14

The Mac version of Relocating the Remains running on Mac OS 9 in the EaaSI (Emulation as a Service Infrastructure) platform managed by New York University libraries, being used in the Chrome browser

I first wanted to compare how EaaSI performed as a remote service in comparison to the Windows virtual machine and Mac OS 9 emulator that ran locally on my Mac laptop (fig.14). The visual quality was the same, and I did not see any compression artefacts or colour changes. However, I did notice that the response rate overall was slower; the mouseŌĆÖs movements around the screen felt laggy, and when I clicked the reaction seemed a beat behind. These changes might not be very important for a researcher looking at a vintage Word document in its native environment, but for interactive content, and especially for artwork content, changes in behaviour can affect the experience and understanding of the work.

Concurrent to my remote placement with Tate, I also had a part-time placement with the Media Conservation team at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. I was able to use resources in MoMAŌĆÖs media conservation lab to do further tests with the Relocating the Remains CD-ROM. I opened the CD-ROMŌĆÖs executable file for PC on a Dell desktop computer with Windows 10, and did not encounter any issues running the work. An advantage to PC is that the underlying architecture and operating systems havenŌĆÖt changed drastically over the years, so compatibility of older files is not as much of an issue as with Macs.[i]

I was excited to test the CD-ROM on a legacy Power Mac G4 running OS 9, which would have been available when Relocating the Remains was released. I had not yet been able to experience content directly from the CD-ROM in a Mac environment while working from home. The interactive animations were slow to react, and loading times were very slow when accessing different parts of the work. I believe this was related to the relatively slow read time of the older optical disc drive in the Power Mac G4, compared to the new Mercury OWC Pro USB disc drive that I had been using. The laser in the disc drive must physically jump around to the location of information on the optical disc as one interacts, so a slow reading speed will translate directly to slow performance of graphics and interactive elements.

This legacy Mac experience lent some perspective to the notion of ŌĆśoriginal behaviourŌĆÖ since it was not as efficient and responsive as I had seen in other computing environments. The whole system, from the optical disc drive, to the available memory, to possible other software running at the same time, might affect the behaviour of a program running from CD-ROM. Considering authenticity to this degree can be quite complicated in terms of deciding just what qualities are important to the experience of digital media.

Feedback from Keith Piper

Having tested Relocating the Remains in several computing environments, from a legacy Mac computer, to virtual machines running Windows 2000, emulators running OS 9 and OS X, and Windows 10 on a contemporary PC, I had seen that there were some differences among them. The legacy Mac computer was a bit slow and glitchy, the Windows version did not have the same level of interactivity in the artwork elements, and the emulated OS 9 version seemed to work very smoothly with full functionality. For these reasons, I would probably choose the OS 9 emulation if I had to pick one method of access for this content, but it was uncertain whether the artist would be open to viewing this work using a disk image and emulation software.

We invited Keith Piper to join a Zoom meeting where I could demonstrate the OS 9 emulation with SheepShaver through screen sharing. It was not an ideal situation because of the risk of network lag and glitches, added compression artefacts, and the fact that only I could interact with the work. Thankfully, it all worked well enough that Piper was excited to see his work revived. He was impressed with the quality of the emulation and commented that it looked just like what he remembered of the original. He shared that other efforts to create an accessible version of Relocating the Remains had experienced problems with transitions and incorrect colour palette.

We discussed some problems with the PC version of the piece such as no rollover responses with animation and sound, as well as some colour differences. Piper said that the PC version was created in 1999 (the piece was originally made in 1997 for Mac only), and he had never paid much attention to it because he only ever used a Mac computer. This would seem to indicate that the PC version should not be prioritised for preservation and access because it never performed correctly in the first place.

We also discussed some display options should the piece ever be exhibited with an emulator, and Piper was not interested in using legacy equipment to keep the work anchored in the context of its original time period. He said that a monitor and mouse in a gallery setting would be sufficient for interaction, since a user being able to navigate through the project and experience the content has always been the main point of Relocating the Remains. I left the meeting satisfied that the artist was happy with how his work was presented in the emulator. One deliverable for this research project will also be a Mac Mini prepared with SheepShaver and the disk image of Relocating the Remains, which will provide access to the work through ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs library.

Conclusion

Proponents of media art history have always known that artistic content on CD-ROMs should be kept accessible, at least in some form. Digital media scholar and technologist Sandra Fauconnier created ŌĆśŌĆÖ in 2012ŌĆō13 on Tumblr as ŌĆśan initiative to safeguard artistic CD-ROMs from the 1990sŌĆÖ, because she was aware that the format was already becoming obsolete.[ii] She discussed using emulators, but also presented GIFs, still images, and screen recording videos on the site as an easy and more publicly archival way to experience the works, at least in part. As discussed in this report, awareness of artistic CD-ROM content is also a key component of keeping it going.

While resources like ŌĆśThe CD-ROM CabinetŌĆÖ are invaluable as an archival record and outreach tool, access to these works in their entirety, and in an interactive state, would better serve the works and those who are interested in them. This project has shown that emulation can be a way to show artistic CD-ROM content while maintaining authenticity, although it is difficult to generalize because of the immense variety of technologies and asset types used on them.

Because artistic content requires closer attention to how the work is displayed, how it appears, and how it behaves, it is unlikely that large-volume approaches to disk imaging and emulation will retain the highest degree of authenticity in all cases. CD-ROMs continue to require advocacy and some specialised skills to come out of their dormant states on optical discs, but I hope this research has shown the rewarding outcomes of those efforts and their value to audiences and the historical record alike.

Additional outreach and dissemination

In addition to demonstrating the emulated version of Relocating the Remains to Keith Piper, I have also shared the results of my research with internal stakeholders at Tate within Curatorial, Conservation, and Library and Archive departments. I have also included those involved in the original commissioning of the work at both Iniva and the Art 360 Foundation.

Resources

Optical Media Preservation Research

US Library of Congress CD-ROM Longevity Research:

Fred R. Byers (ed.), ŌĆśCare and Handling of CDs and DVDS: A Guide for Librarians and ArchivistsŌĆÖ, Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), 2003.

Fred R. Byers, ŌĆśHow Long Can You Store CDs and DVDs and Use Them Again?ŌĆÖ

Tina Sieber, ŌĆśCDs Are Not Forever: The Truth About CD/DVD LongevityŌĆÖ,

CD-ROM access projects

The CD-ROM Cabinet:

Theresa Duncan CD-ROMs at Rhizome:

Geoffrey Brown, ŌĆśDeveloping Virtual CD-ROM Collections: The Voyager Company PublicationsŌĆÖ, International Journal of Digital Curation, vol.7, no. 2 (December 2012), pp.3ŌĆō20,

Kam Woods and Geoffrey Brown, ŌĆśCreating Virtual CD-ROM CollectionsŌĆÖ, International Journal of Digital Curation, vol.4, no. 2 (1 October 2009), pp.184ŌĆō98,

Public Disk Imaging Workflows

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Conservation Department, ŌĆśWorkflow for Disk ImagingŌĆÖ,

Tom Ensom, Time-based Media Conservation, Tate, ŌĆśDisk Imaging GuideŌĆÖ, /documents/3/sbapp_disk_imaging_guide_01_00.pdf

Eddy Colloton, ŌĆśDenver Art Museum Disk Imaging WorkflowŌĆÖ,

ŌĆśPeer Forum I: Disk ImagingŌĆÖ (7ŌĆō8 December 2017 at MoMA),

Getty Institutional Records and Archives, ŌĆśAccessioning Files from CDs and DVDsŌĆÖ,

van der Knijff, ŌĆśImage and Rip Optical Media Like a Boss.ŌĆÖ Open Preservation Foundation.

van der Knijff, Johan. ŌĆśPreserving optical media from the command-line.ŌĆÖ

van der Knijff, Johan. ŌĆśCD and DVD imaging and quality control notes.ŌĆÖ

Disk Imaging Tools

BitCurator Environment (Linux):

- disktype command line tool

- Guymager disk imaging software

DVDisaster (Linux):

Ddrescue (Linux):

IsoBuster software (Windows):

AnyBurn software (Windows):

Disk Utility (Mac):

dd (Data Duplicator) command line tool (Mac):

Aaru (or DiscImageChef) command line tool (Windows, Linux, macOS):

ŌĆśDisk Image Format MatrixŌĆÖ (spreadsheet, deliverable for Harvard Library), AVP, 16 Apr. 2016,

Emulators

SheepShaver:

- An open source emulator of PowerPC Macintosh computers for Windows, OS X and Linux.

- Boot Mac OS 7.5.2 through 9.0.4.

Basilisk II:

- An open source emulator of 68xxx-based Macintosh computers for Windows, OS X and Linux.

- Boot Mac OS versions 7.x through 8.1.

Mini vMac:

- An open source emulator of 68000-based Macintosh computers for Windows, OS X and Linux.

- Macintosh Plus, 128K, 512K, 512Ke, SE and Classic models.

Qemu: or

- An open source emulator for a variety of guest operating systems, run from the command line on Windows, OS X and Linux.

- Qemu ŌĆśScreamerŌĆÖ fork for OS 9 audio (macOS and Windows):

Emulation as a Service Infrastructure (EaaSI):

Bibliography

Moving Image Archiving and Preservation MA programme at New York University, ŌĆśHandling Complex MediaŌĆÖ course student research:

- Brad Campbell: (2005)

- Paula F├®lix-Didier: (2005)

- Sean Savage: (2005)

- Kara van Malssen: (2005)

- Lynley-Shimat Lys: (2006)

- Loni Shibuyama: (2006)

- Sandra Gibson and Jonah Volk: (2010)

Amelia Acker, ŌĆśEmulation Encounters: Software Preservation in Libraries, Archives, and Museums,ŌĆÖ Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology 57, no.1 (October 2020), pp.1ŌĆō10, .

ŌĆśAdobe DirectorŌĆÖ, Wikipedia, .

D. Alexander, M. Casad and D. Dietrich, ŌĆśŌĆŗŌĆŗCreating a Preservation and Access Framework for Digital Art ObjectsŌĆÖ, Electronic Media Review Volume 3 (2013ŌĆō2014), .

Geoffrey Brown, ŌĆśDeveloping virtual cd-rom collections: The voyager company publications.ŌĆÖ International Journal of Digital Curation, vol.7, no.2 (2012), pp.3ŌĆō22, .

Marc Canter, ŌĆśThe New Workstation: CD-ROM Authoring SystemsŌĆÖ in Multimedia: from Wagner to virtual reality, edited by Randall Packer and Ken Jordan (New York 2001), pp.179ŌĆō88.

M. Casad, O.Y. Rieger and D. Alexander, ŌĆśEnduring Access to Rich Media Content: Understanding Use and Usability RequirementsŌĆÖ, D-Lib Magazine (September ŌĆō October 2015), .

CRUMB ŌĆō Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss, .

Gratien DŌĆÖhaese, ŌĆśThe ISO 9660 FileSystemŌĆÖ, Dubeyko.com (May 1995) .

Angela Dappert, Andrew Jackson and Akiko Kimura, ŌĆśDeveloping a Robust Migration Workflow for Preserving and Curating Hand-held MediaŌĆÖ, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Digital Preservation, iPRES 2011, Singapore, 1ŌĆō4 November 2011, .

Michael Day et al., ŌĆśThe Preservation of Disk-Based Content at the British Library: Lessons from the Flashback ProjectŌĆÖ, Alexandria, vol.26, no. 3 (1 December 2016), pp.216ŌĆō34, .

A. Dekker and P. Falcao, ŌĆśInterdisciplinary Discussions about the Conservation of Software-Based ArtŌĆÖ, PERICLES, Tate, .

Janet Delve, Preserving Complex Digital Objects, London.

Dianne Dietrich et al, ŌĆśHow to Party Like It Is 1999: Emulation for EveryoneŌĆÖ, The Code4Lib Journal, no. 32 (April 2016), .

Brian Dietz and Shira Peltzman, ŌĆśDeveloping an Access Strategy for Born Digital Archival Material,ŌĆÖ Digital Preservation Coalition (2021) .

ŌĆśDigital Archives Technical Glossary (v 1.0.0)ŌĆÖ, DANNNG ŌĆŗŌĆŗ(Digital Archival traNsfer, iNgest, and packagiNg Group; 2022), .

ŌĆśDisk Imaging Decision Factors (v 1.0.1)ŌĆÖ, DANNNG ŌĆŗŌĆŗ(Digital Archival traNsfer, iNgest, and packagiNg Group; 2022), .

Jackie Dooley, ŌĆśViewpoint: How ŌĆśSpecialŌĆÖ Are Born-Digital Collections?ŌĆÖ Art Libraries Journal, vol.35, no.3 (2010), pp.3ŌĆō4, .

Nina van Doren and Alexandre Michaan, ŌĆśCD-ROM Archiving. Archiving and Distribution of CD-ROM Artworks, a Study of the Emulation as a Service (EaaS) Tool and Other ProposalsŌĆÖ, Zenodo (1 November 2016), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4319066.

Alex Duryee, ŌĆśAn Introduction to Optical Media PreservationŌĆÖ, .

D. Espenschied et al., ŌĆśLarge-Scale Curation and Presentation of CD-ROM ArtŌĆÖ, iPRES 2013 (2013), .

D. Espenschied et al., ŌĆś(Re-)publication of Preserved, Interactive Content ŌĆō Theresa Duncan CD-ROMs: Visionary Videogames for Girls,ŌĆÖ iPRES 2015 annual meeting, 2015 Nov 2-6; Chapel Hill, NC (2015), pp.233ŌĆō34, .

P. Falcao, A. Dekker and P. Laurenson, ŌĆśAn Exploration of Significance, Dependency, and Virtualization in the Conservation of Software-based Artworks,ŌĆÖ Electronic Media Review Volume 4 (2015ŌĆō2016), .

Sandra Fauconnier, ŌĆśThe CD-ROM Cabinet after 6 MonthsŌĆ”.ŌĆÖ Aaaan.Net (10 October 2013), .

Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media (Cambridge, MA, 2022).

M. Guttenbrunner and A. Rauber, ŌĆśA measurement framework for evaluating emulators for digital preservationŌĆÖ, ACM Transactions on Information Systems, vol.30, no.2, pp.14:1ŌĆō14:28 ( May 2012), .

Aniko L. Halverson and Joye Volker, ŌĆśThe Integration of Computer Services with Academic Arts Libraries: New Strategies for the Hybrid ProfessionalŌĆÖ, Art Libraries Journal, vol.26, no.3 (2001), pp.8ŌĆō13, .

Sarah Haylett, ŌĆśArchives and Record ManagementŌĆÖ, published as part of the research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, Tate, 2019, /research/reshaping-the-collectible/research-approach-archives-record-management.

Margaret Hedstrom and Clifford Lampe, ŌĆśEmulation vs. Migration: Do Users Care?ŌĆÖ RLG Diginews, vol.5 (2001), p.7, .

Margaret Hedstrom et al., ŌĆśThe Old Version Flickers More: Digital Preservation from the UserŌĆÖs PerspectiveŌĆÖ, American Archivist, vol.69, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2006), pp.159ŌĆō87, .

P. Innocenti, ŌĆśRethinking authenticity in digital art preservationŌĆÖ, 9th International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects (iPRES2012), University of Toronto (2012), pp.63ŌĆō67. .

Mona Jimenez, ŌĆśInteractive Multimedia on CD-ROM: Experiments with Risk AssessmentŌĆÖ, Qu├®bec, Canada (2008), .

ŌĆśJohn Henry Thompson: Computer Programming and Software InventionsŌĆÖ, n.d. Famous Black Inventors, .

Julia Y. Kim, ŌĆśResearcher Access to Born-Digital Collections: an Exploratory StudyŌĆÖ, Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, vol.5, article 7 (2018), .

ŌĆśLevels of Born-Digital AccessŌĆÖ, The Digital Library FederationŌĆÖs Born-Digital Access Working Group (2020), .

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum et al., ŌĆśDigital Forensics and Born-Digital Content in Cultural Heritage CollectionsŌĆÖ, CLIR Publication, no.149, Washington, D.C: Council on Library and Information Resources (2010), .

M. McKeehan, ŌĆśIntellectual Property Rights Issues for Software Emulation: An Interview with Euan Cochrane, Zach Vowell, and Jessica MeyersonŌĆÖ, The Signal: Digital Preservation (2016), .

Sharon McMeekin, ŌĆśUnderstanding User NeedsŌĆÖ, Digital Preservation Coalition (7 September 2021) .

Mediamatic art centre online archive, ŌĆścd-romŌĆÖ search, .

Julia Noordegraaf et al. (eds.), Preserving and Exhibiting Media Art: Challenges and Perspectives, Amsterdam University Press, 2013.

Eoin OŌĆÖDonohoe, ŌĆśEmulation as a Service for heritage institutes. Test report (1.0)ŌĆÖ, Zenodo (2020), .

Keith Piper and Kobena Mercer, Relocating the Remains (London 1997).

Mary Pagliero Popp and A.F.M. Fazle Kabir, ŌĆśCD-ROM Sources in the Reference CollectionŌĆÖ, The Reference Librarian, vol.13, no.29 (8 October 1990), pp.77ŌĆō91, .

K. Rechert, I. Valizada and D. von Suchodoletz, ŌĆśFuture-proof preservation of complex software environmentsŌĆÖ, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects (iPRES2012), University of Toronto Faculty of Information (2012), pp.179ŌĆō83, .

Klaus Rechert, Patricia Falcao and Tom Ensom, ŌĆśIntroduction to an Emulation-Based Preservation Strategy for Software-Based ArtworksŌĆÖ, Tate, /about-us/projects/pericles/emulation-based-preservation-strategy-for-software-based-artworks.

J. Rees, ŌĆśDigital Interactive Publishing: Off- and On-line, Some ObservationsŌĆÖ, Art Libraries Journal, vol.24, no.1 (1999), pp.33ŌĆō39, doi:10.1017/S0307472200019313.

O. Rieger and M. Casad, ŌĆśInteractive digital media art survey: Key findings and observationsŌĆÖ, DSPS Press (blog), Cornell University, New York (2014), .

Oya Y. Rieger et al., ŌĆśPreservation and Access Framework for Digital Art ObjectsŌĆÖ, Cornell University Library, New York, .

David S.H. Rosenthal, ŌĆśEmulation & Virtualization as Preservation StrategiesŌĆÖ, .

Michelle Rothrock, Alison Rhonemus and Nick Krabbenhoeft, ŌĆśAssessing High-Volume Transfers from Optical Media at NYPLŌĆÖ, The Code4Lib Journal, no. 51 (14 June 2021), .

Annie Schweikert, ŌĆśAn Optical Media Preservation Strategy for New York UniversityŌĆÖs Fales Library & Special CollectionsŌĆÖ (2018), .

C.J. Shahani, M.H. Youket and N. Weberg, ŌĆśCompact Disc Service Life: An investigation of the estimated life of prerecorded compact discs (CD-ROM)ŌĆÖ (2009), .

Gilane Tawadros, The Sphinx Contemplating Napoleon: Global Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Difference (London 2020).

Simon Whibley, ŌĆśFlashpoint: Back in a Flash II,ŌĆÖ Open Preservation Foundation (2016), .

Kam Woods and Geoffrey Brown, ŌĆśCreating Virtual CD-ROM CollectionsŌĆÖ, International Journal of Digital Curation, vol.4, no.2 (1 October 2009), pp.184ŌĆō98, .