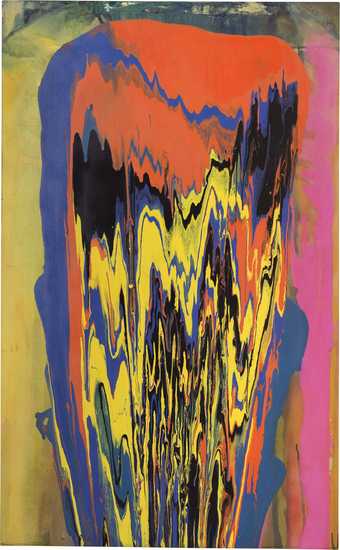

Kenneth Martin

Seventeen Lines (1959–63)

Tate

Drawing a line is the way we all learn to draw. When we make our very first marks as children, the pleasure is in the lines and scribbles we produce. These simple lines can become much more though. Our brains are so trained to look for patterns, we can see movement and shape all from a few simple marks on a page.

Mark Making

You can use lines in lots of different ways to create shapes, to build up areas of shadow or tone - to trace form or even to suggest movement.

How you make your lines changes how we ‘read’ them. Varying the weight of your line (how heavily you press with your pen or pencil) can give a sense of depth or movement, making some lines come towards you and others recede.

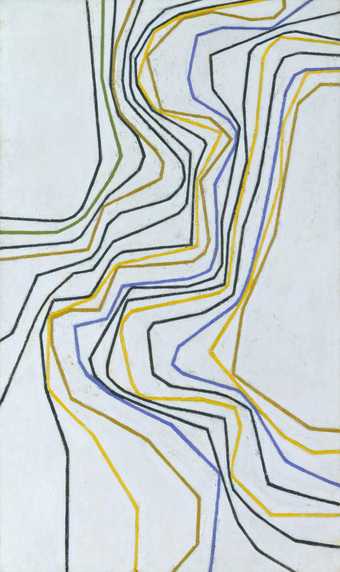

Richard Deacon

Untitled Drawing (1980)

Tate

Some drawing materials don't really give you a varied line. Using something like a fineliner you can instead use the placement of the lines you draw to give a feeling of space or texture.

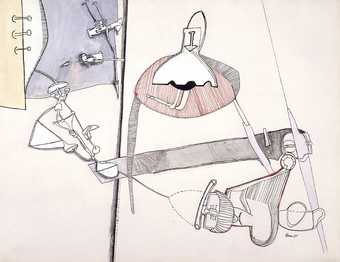

Where Eva Hesse’s graphic lines are placed close together they make us see shape and form. Maybe there is a shadow behind that flapping curtain, or perhaps it’s a fringe on a blanket. Some of the pipe shapes seem to be squashy, while others, with fewer lines, look hard or rigid.

Eva Hesse

Untitled (1965)

Tate

© The estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Zürich

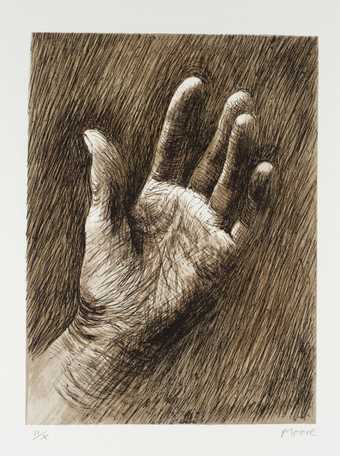

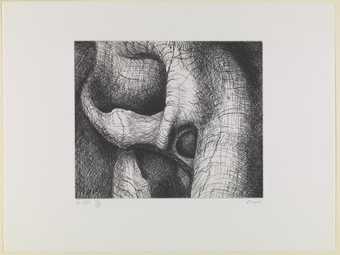

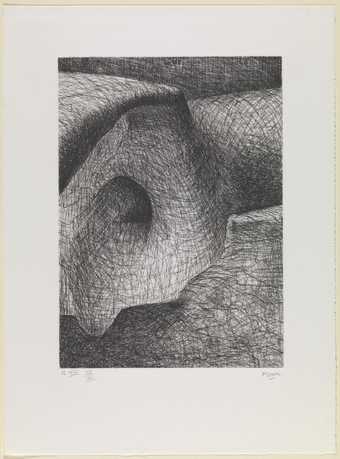

Henry Moore uses repeating lines criss-crossing each other to bring out the form of a skull bone. The more lines he uses the more we see the depth of shadows. The less-lined areas pop out as highlights. Notice how his marks don’t always follow the contours of the bone, but all the marks together bring the form to life.

Henry Moore OM, CH

Elephant Skull Plate XXV (1970)

Tate

Henry Moore OM, CH

Elephant Skull Plate XVI (1970)

Tate

Mark making isn’t always representational though. Sometimes it's more about the process of making the mark itself.

Rebecca Horn

Pencil Mask (1972)

Tate

Imaginative Lines

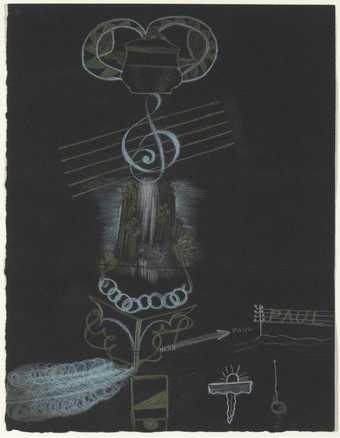

André Breton, Nusch Eluard, Valentine Hugo, Paul Eluard

Exquisite Corpse (c.1930)

Tate

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS 2025, London; © Estate of Paul Eluard

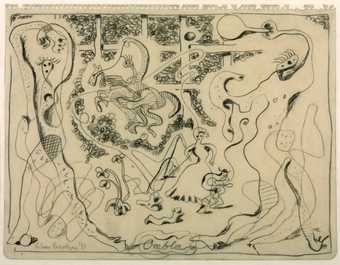

Have you ever played 'Heads, Bodies, Legs'? Where you draw one part of a person or animal on a piece of paper and then pass it on to someone else to draw the next part? This was a technique invented by the Surrealists to try to create a new sort of drawing. Surrealism was an artistic movement of the early 1920s, and these artists and writers didn't want to represent the visible world around them. Instead they wanted to tap into imaginative or unconscious dream worlds.

Surrealists came up with lots of techniques to try to unlock their unconscious minds – and bring out the hidden creativity within them. One was collaborating on these drawings they called ‘cadavres exquis’ (which means ‘exquisite corpse’ in French) – a lot like 'Heads, Bodies, Legs', except you could draw absolutely anything. (You could try playing this with other friends taking the same options as you – sending your drawings through the post).

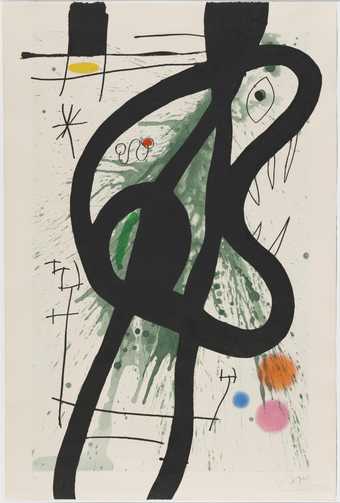

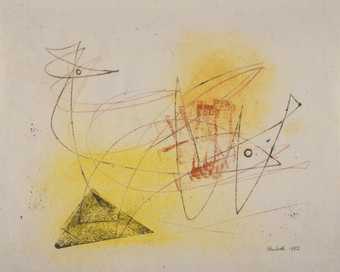

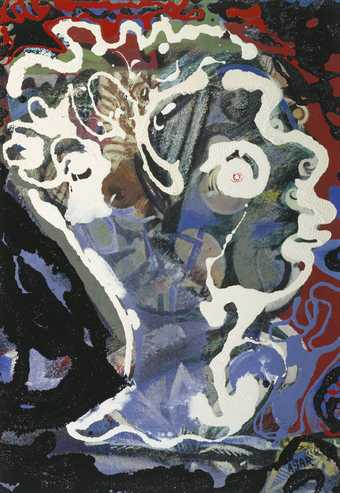

But Andre Breton and other Surrealists also practiced what they called automatic writing or drawing. They tried to write or draw without thinking about what they were doing, and letting their hands just draw whatever came out of them! It’s really a type of doodling! They thought this would tap into their dream worlds and create new worlds in their art. Lots of artists since have also tried this sort of automatic drawing: just letting a line ‘go for a walk’ and seeing what comes out of it.

Joan Miró

The Great Carnivore (1969)

Tate

John Wells

Untitled Drawing (1952)

Tate

Julian Trevelyan

Ombla (1931–2)

Tate

Eileen Agar

Head of Dylan Thomas (1960)

Tate

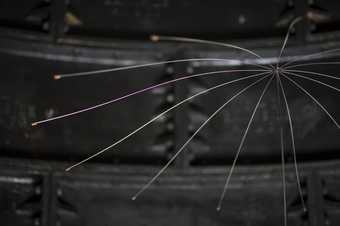

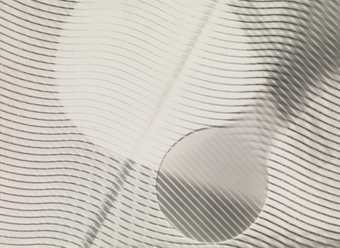

Lines in space

Lines can also translate from the page to the 3D world of sculpture. Some sculptors use lines in their works, both while drawing studies to to work from and actually in their finished forms. A line can be visible, and made into three dimensions in wire or wood. Or it can be invisible, drawn through space by movement, or even created by the play of light or the spaces between sculptural forms.

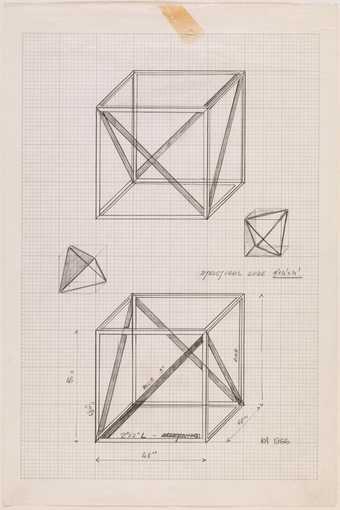

Rasheed Araeen

Drawing for Sculpture (1966)

Tate

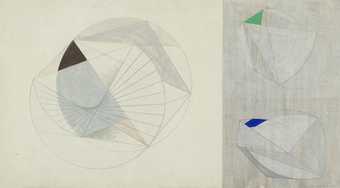

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Drawing for ‘Sculpture with Colour’ (Forms with Colour) (1941)

Tate

Peter Logan

Square Dance (1970)

Tate

Wen-Ying Tsai

Umbrella (1971)

Tate

Luigi Veronesi

Construction (1938)

Tate

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Poem of Nine Verses (1966–8)

Tate

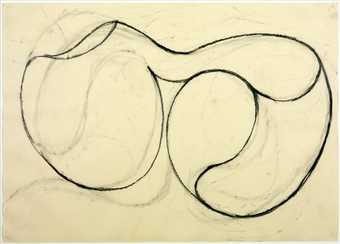

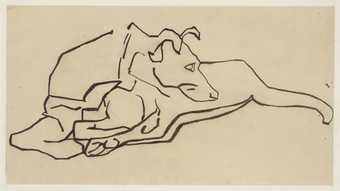

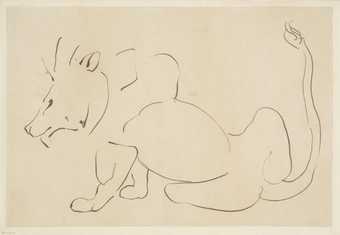

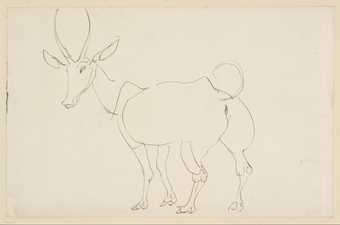

Fast and Fluid

Using simple lines can be a way of getting the feeling of a subject down on paper quickly. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was a master of this sort of quick sketch. His fluid, fast lines create recognisable and characterful shapes and forms with the smallest number of marks.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Jaguar (³¦.1912–13)

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Studies of Birds (³¦.1912–13)

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Vulture II (³¦.1912–13)

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

A Dog (c.1913)

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Lion (³¦.1912–13)

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Eland (³¦.1912–13)

Tate

He often sketched at London Zoo in Regent’s Park – quickly jotting down the animals as they paced and moved. He used pen and ink – perfect for quick flowing lines. It’s a good practice to get into, drawing as quickly as you can. It loosens up your muscles and forces you to look at the most essential lines you need to get your idea or form across.