A little like proverbial trees falling in forests, does art speak if no-one is around to hear it?

I think it is quite rare to think about how art speaks. Perhaps we think we are doing it all the time when we look at, talk about, write about art. Over the years, however, I found I was doing something entirely different. Rather than thinking about how art speaks, I was thinking about how to speak about art. Of course, the two overlap. Slipping and sliding over each other until I find it impossible to think about one without the other. But they are not the same. After sitting with these questions for a few months, I realised that thinking about how art speaks is actually incredibly freeing. There is no reason to be self-conscious when thinking about how art speaks, no particular need to have done the reading or read the reviews. Doing these things may alter how art speaks to you, in positive and negative ways. But, even without them, the conversations you can have with art can be deep, personal, frivolous, intimate. And they will be influenced by who you are and who youŌĆÖre with, where the art is displayed and how long itŌĆÖs been since lunch.

In the past, I focused too much on how to speak about art. I tried to convey through my writing what I thought art was saying ŌĆśgenerallyŌĆÖ. Tried to imagine what other people might want me to say about it. I was scared to honestly recount the conversations I was having with art in case the way art spoke to me was ŌĆśwrongŌĆÖ or perhaps revealed too much. This text offers some ways that art might speak to you and some ways it has spoken to me, but, as ever, the best way to hear what art has to say is by listening, looking, participating and imagining.

Lyle Ashton Harris

Speaking Through Photography

Lyle Ashton Harris

Constructs #10 - #13 (1989)

Lent by the Tate Americas Foundation, purchased with funds provided by the North American Acquisitions Committee, The Agnes Gund Fund and Salon 94 2019

IŌĆÖm standing in ╔½┐ž┤½├Į in front of Constructs #10 - #13 (1989), Lyle Ashton HarrisŌĆÖs series of four black and white self-portraits. I look up and unexpectedly catch his eye in the photograph on the far left. He looks straight back at me, assertive in his netted tutu and ballet pose. Even when facing away from me in the second photograph, I feel like he is in control of the conversation. He appears to communicate his attitude through the sway of his hip, his tousled wig, and the netted material that barely covers his behind. He seems at ease, confident in front of the camera. But the last in the series is different. This time, instead of him choosing to turn away, it feels as though IŌĆÖm the one who has decided to watch him from behind. The power has shifted to me, as his body shows none of the attitude marked by clothes or pose so evident in the other photographs. He doesnŌĆÖt speak to me and instead I am left to project onto him, almost a blank canvas.

Across the four photographs, Harris plays with the language of classical sculpture and ballet: art forms with high cultural value. But, as a gay Black man making this work at the height of the AIDS pandemic, he subverts this language of established power. Harris has described the photographs as ŌĆ£almost an aggressive assertion of sex positivenessŌĆØ and ŌĆ£a tool for embodiment to reimagine the self [...] and rethink our understanding of identity.ŌĆØ Made while he was still a student in California, the series has become some of his most celebrated work, included in exhibitions such as Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art curated by Thelma Golden in 1994 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In a conversation with artist and writer Morgan Quaintance, Harris described how his work and the Whitney exhibition made a lasting impact on many who saw it at a time when Black and queer identities were not very visible in mainstream art spaces.

The great [artist] Kehinde Wiley said it was seeing that work at the Whitney, Thelma Golden's landmark show, that did something for him in terms of speaking about the possibility of gender. Or the curator of media at MoMA, Thomas Lax, my dear friend, who said seeing that work as a teenager, it resonated and it caused a rupture in terms of his thinking.

Lyle Ashton Harris in conversation with artist and writer Morgan Quaintance at a Tate event

HarrisŌĆÖs art is both the product and creator of many conversations between artists and artworkers and this is integral to how he speaks about his art and career. His work forms part of a dialogue between a network of Black creatives and thinkers, including filmmakers, artists, poets and theorists, many of whom he first met when they were visiting lecturers at the California Institute of Arts (CalArts). He took a one-week seminar led by writer bell hooks on the theme of ŌĆ£talking backŌĆØ. For Harris, ŌĆ£being exposed to that book, what it meant to be able to speak in my own language, in my own voice, became a way in which I began to somehow seek out other forms of community, etc.ŌĆØ

We have to also transport ourselves back to LA where CalArts is situated, where I was one of a few people of colour and what it meant to negotiate that terrain.┬ĀAnd I think having people, whether that's the great late Marlon Riggs or meeting Isaac Julien or John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, and having them telegraph, if you will, to the professors that ŌĆ£he's one of usŌĆØ - if you think about the idea of care and nurture. And I did as well as an academic, because even today in 2023, where obviously itŌĆÖs much more diverse, the absolute necessity, in terms of pedagogy, to be able to pull forward someone who you might intuitively understand that they might be a messenger of a certain body of knowledge. So I think in a way there was a mutuality.

Lyle Ashton Harris in conversation with artist and writer Morgan Quaintance at a Tate event

Sharon Hayes

Speaking Through Love

Sharon Hayes

Everything Else Has Failed! DonŌĆÖt You Think ItŌĆÖs Time For Love? (2007)

Tate

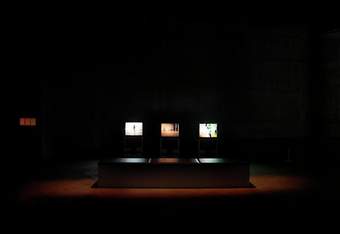

Sharon HayesŌĆÖs work speaks to us in a more literal sense ŌĆō aloud, and with words. Everything Else Has Failed! DonŌĆÖt You Think ItŌĆÖs Time for Love? (2007) is an installation by Hayes that replays "love addresses". Hayes explains that a ŌĆ£love addressŌĆØ captures how she memorised and delivered these passages in the form of letters, as if they were composed on the spot. The installation comprises five PA speakers placed directly opposite five posters advertising the performance, one for each day of the week. From each speaker in turn, we hear HayesŌĆÖs amplified voice above the noise of a busy New York street, speaking to unnamed lover. In the original performance, Hayes stood on a busy corner outside an investment bank in Manhattan, speaking each "love address" aloud to the passing public, repeating each three times. In conversation with writer So Mayer, Hayes described how she wanted to ŌĆ£butch upŌĆØ her appearance for the performance as she hoped the anonymised letters would be interpreted as expressions of queer love. But the ŌĆ£youŌĆØ she addresses in the work remains an open invitation to whoever is listening.

The title of the work Everything Else Has Failed! DonŌĆÖt You Think itŌĆÖs Time for Love? is taken from a placard that was held up during a protest in Berkeley, California in 1967. Over the years, Hayes has amassed a large collection of photographs of protest signs containing the word ŌĆ£loveŌĆØ. For Hayes, the love expressed by these signs ŌĆ£is a commitment, a collective tactic, a vital component of [...] non-violent resistance.ŌĆØ In her work, Hayes uses the intimate language of a personal letter to a lover, but, like with the placards, the implications are different when they are shared publicly. ŌĆ£The letters are not being read to their [original] addressees but to imagined future audiences,ŌĆØ she explained.

ŌĆ£Everything else has failed! Don't you think it's time for love?ŌĆØ I found this image in a very general folder in the picture collection at the Mid Manhattan Library in New York City in probably the early 2000s. I have not seen images of it circulate elsewhere. The love here is not confident or clear. It does not enthusiastically recruit. It pleads. It's doubtful. It's vulnerable. I love it.

Sharon Hayes┬Āperforming ŌĆ£What is Love?ŌĆØ presented as part of a Tate event┬Āwith So Mayer.

┬® Wendy Parker, East Cobb News, Georgia, USA

I see you. I hear you. I stand with you. I love you.

I, as the I who holds the sign, love you, who is not specified. You, who might be marching next to me, or passing by in your car, or walking by me and seeing this, or seeing this image on the internet.

Sharon Hayes┬Āperforming ŌĆ£What is Love?ŌĆØ presented as part of a Tate event┬Āwith So Mayer.

Everything Else Has FailedŌĆ” is the first in a series Hayes calls Love Addresses, a series that speaks of HayesŌĆÖs despair and helplessness ŌĆō and the failure of mass protest ŌĆō in the face of the US war in Iraq and Afghanistan. She is interested in the idea that speech can do more than communicate, it can also perform ŌĆ£speech actsŌĆØ (a theory developed by philosopher J.L. Austin in his 1962 book ŌĆ£How to do things with wordsŌĆØ). Examples of speech acts include apologies, congratulations, invitations or promises, like the words ŌĆ£I doŌĆØ during a marriage ceremony. I like to think HayesŌĆÖs work is a speech act of solidarity, of love. As with protest signs, art is an open invitation that can speak ŌĆō and offer this act of love ŌĆō to anyone who sees it. Hayes explained how to understand the address from a protest placard, you need to look at the words on the sign, the person holding it and the place and time they are in. Although referencing specific political events of 2007, as part of ░š▓╣│┘▒ŌĆÖs collection, the work will now exist across time, preserved by the museum to perform speech acts at potentially infinite future moments.

I went towards love to talk about war, because to arrive on the street with a microphone and a speaker to talk about war did not feel possible actually. It did not feel possible in that moment. And so I do think of this work as a way to speak indirectly to a public or a set of publics that was right in front of me, walking by, but who weren't the literal addressee. So it allowed for a kind of way to sit or stand or listen from or absorb from a place of kind of ethical witnessing rather than from a place of being the ŌĆ£youŌĆØ themselves.

Sharon Hayes in conversation with writer, film curator and organiser So Mayer at a Tate event

Trisha Brown

Speaking Through Movement

I often think of dance as an ephemeral performance, but its life is also prolonged when it enters a museumŌĆÖs collection. Trisha BrownŌĆÖs Set and Reset is a work of post-modern dance first performed in 1983. Brown originally choreographed the piece using a process of memorised improvisation. The improvisation was done to a set of five instructions from Brown: ŌĆ£keep it simple, act of instinct, stay on the edge, work with visibility and invisibility, and get in lineŌĆØ. Carolyn Lucas (Associate Artistic Director of Trisha Brown Dance Company) explained how dancers must learn a new vocabulary of dance in order to master the choreography, putting together memorised phrases of movement to create longer passages.

Trisha develops movement vocabulary. So she always starts with phrase work. And then she's thinking, What am I going to do with these phrases? And that's pretty much her motor through the trajectory of her career, itŌĆÖs always to make the vocabulary first.

Carolyn Lucas in a Tate event panel discussion about Trisha BrownŌĆÖs 1983 dance Set and Reset

Watching the performance, I feel like I am experiencing improvisation, full of the happy coincidences that occur when a group of people know each other so well that they are in tune with each otherŌĆÖs movements, like when you adopt a tilt of the head from your mother or an eyebrow raise from your best friend. In discussion with Carolyn Lucas, dancer Joel Brown and Director of Programme Catherine Wood, Benoit-Swan Pouffer (Artistic Director of Rambert) spoke about bodies being collectors of experiences. There is the physical memory of the dance choreography but also the memories of how the body has moved before, both through dance and in the world in general. The end performance expresses all of these experiences, this knowledge. In the original performance of the piece, we can compare the movement of Eva Karczag, a dancer who brought her traditional ballet training to her movement, to Trisha Brown, whose movements were deliberate refusals of balletŌĆÖs strict language.

I just do believe that the more [dancers] get into a work, the more [...] they immerse themselves in the work, they're going to leave with something. [...] It makes them richer. It makes them collectors and thatŌĆÖs what we all are as dancers.

Benoit Swan Pouffer in a Tate event panel discussion about Trisha BrownŌĆÖs 1983 dance Set and Reset

The choreography speaks across generations to other communities of dancers. Dancer Joel Brown, who performs a version of Trisha BrownŌĆÖs choreography called Set and Reset/Reset with Candoco Dance Company, spoke of his excitement that Set and Reset would be kept alive through new dancers who will need to learn the choreography every time the piece is brought out for ŌĆ£displayŌĆØ.

I feel a connection or a history or a shared knowledge with other people who also know this knowledge. But I have this fantasy of being a really old man in a wheelchair. And thereŌĆÖs hopefully some young dancers learning this work, and I just join them.

Joel Brown in a Tate event panel discussion about Trisha BrownŌĆÖs 1983 dance Set and Reset

GeeŌĆÖs Bend

Speaking Through Community

Aolar Mosely

ŌĆ£Log CabinŌĆØ - single block ŌĆ£Courthouse StepsŌĆØ variation (local name: ŌĆ£BricklayerŌĆØ) (c.1950)

Lent by the Tate Americas Foundation 2022

In GeeŌĆÖs Bend, Alabama, the skill of quiltmaking has been passed down through generations of African-American women since the 19th century. Seeing these quilts in a gallery, I am very aware that many were made to be used, not to be seen in the white cube of a contemporary art space. The quilts were traditionally taken outside after the winter months to be aired out and were laid over washing lines and fences to be examined and enjoyed by neighbours. They contain the material evidence of the mundane and everyday, of special memories and loved ones passed away. They make me think of the cloth that has held important places in my life ŌĆō a blanket given to me by my nana, a t-shirt I kept for years after I outgrew it. A different kind of beauty is found in wear and in age, in something that has meant many different things to different people over its life and theirs.

Until the middle of the 20th century, the majority of patchwork quilts from the area were constructed from the remains of ragged shirts, dress bottoms and worn out denim work trousers. This is what we refer to as the work-clothes quilt. And in a way, these work-clothes quilts really provide a tangible record of lives lived in the community and is part of that kind of constancy of understanding of self, of community and also of history. There is something really profoundly autobiographical about these works. The ancestors are still there keeping you warm. They act as these extended family portraits, in a sense. In Gee's Bend, this recycling practice really became the founding ethos for generations of quiltmakers who have transformed this otherwise useless material into the marvels that we see now all around the world.

Raina Lampkins-Fielder in conversation with art historian and curator artist Alayo Akinkugbe about The GeeŌĆÖs Bend quiltmakers at Tate event

Most quilts from GeeŌĆÖs Bend can be considered ŌĆ£my wayŌĆØ quilts. Speaking with art historian Alayo Akinkugbe, curator Raina Lampkins-Fielder explained how ŌĆ£the quilter starts with basic forms and then heads off ŌĆ£their wayŌĆØ, allowing the material to really direct their hand with unexpected patterns, unusual colours, and surprising rhythms, really seeing where the quilt takes youŌĆØ. There are also many popular quilt styles including ŌĆ£house topŌĆØ, a pattern of concentric squares that begins with a medallion of solid cloth to which rectangular strips of cloth are added. Aolar MoselyŌĆÖs quilt ŌĆ£Log CabinŌĆØ ŌĆō single block ŌĆ£Courthouse StepsŌĆØ variation (local name: ŌĆ£BricklayerŌĆØ) (c.1950) is a particular adaptation of the house top style, which in GeeŌĆÖs Bend is called ŌĆ£bricklayerŌĆØ. The quilt is hung like a painting in the gallery, but I imagine what it would be like to look down on it from above, like the aerial view of the housetop it depicts. I see the stains faded by time and imagine a time long ago, a clumsy child spilling a drink and scolded by their mother who had spent so long crafting together the scraps of material.

The quilts do not just reveal individual and family histories preserved in the materials but they also record the history of the community. The Freedom Quilting Bee was a sewing co-operative to which many of the GeeŌĆÖs Bend quilters belonged. In 1972, Sears Roebuck, a nationwide retailer in the US, commissioned the co-operative to create corduroy pillow covers. You can now see this commercial enterprise reflected in the gold, avocado leaf, tangerine and cherry red corduroy used in many quilts around that time ŌĆō offcuts and scraps from the commission that the women saved from the floor and shared with other quilters in the community.

The way that art has been and continues to be categorised can change the way it is received. Artists from GeeŌĆÖs Bend have often been described as ŌĆ£self-taughtŌĆØ, a label Raina Lampkins-Fielder believes ŌĆ£doesnŌĆÖt have a bearing on the work that these artists are producing.ŌĆØ The term self-taught not only affects the way that people perceive the art but also affects peopleŌĆÖs ability to talk about it, giving the impression that this artform has sprung up from nowhere and has no relationship to the rest of art history.

[The term self-taught means that] work might not be shown in a museum in a certain way, that there might not be curators who are able to work with those works of art. They might not be written about. That information about these artists won't be disseminated as widely. [...] The fair market value of their work will be significantly diminished by all of these titles.

Raina Lampkins-Fielder in conversation with art historian and curator artist Alayo Akinkugbe about The GeeŌĆÖs Bend quiltmakers at Tate event

End Thoughts

Writing this piece has allowed me to spend time with these works and reflect on how they speak to me personally and how that conversation relies on so much more than the artwork itself. There are many power structures at play that shape our perception of art, and influence where it is shown, how it is described, and even who is open to listening to it. The works by Lyle Ashton Harris, Sharon Hayes, Trisha Brown and the GeeŌĆÖs Bend quiltmakers have sparked conversations between artists, historians, curators and dancers about how art can speak in todayŌĆÖs world. ItŌĆÖs exciting to think about how these artworks might generate new conversations with future generations, to speak in ways we canŌĆÖt yet imagine.

About Debbie Meniru

Debbie Meniru is a London-based writer and curator who explores art and museums through emotion, anecdote and humour. Her writing has been published internationally and you can read more on .

The How Does Art Speak? Series is part of the Terra Foundation for American Art Series: New Perspectives